Anne Frank’s stepsister, Eva Schloss, recounts horrors of Auschwitz 75 years after liberation

The peace activist and international speaker recounts how she was torn from her happy childhood in Vienna and ‘saved’ from the concentration camp’s angel of death, Josef Mengele, by a hat

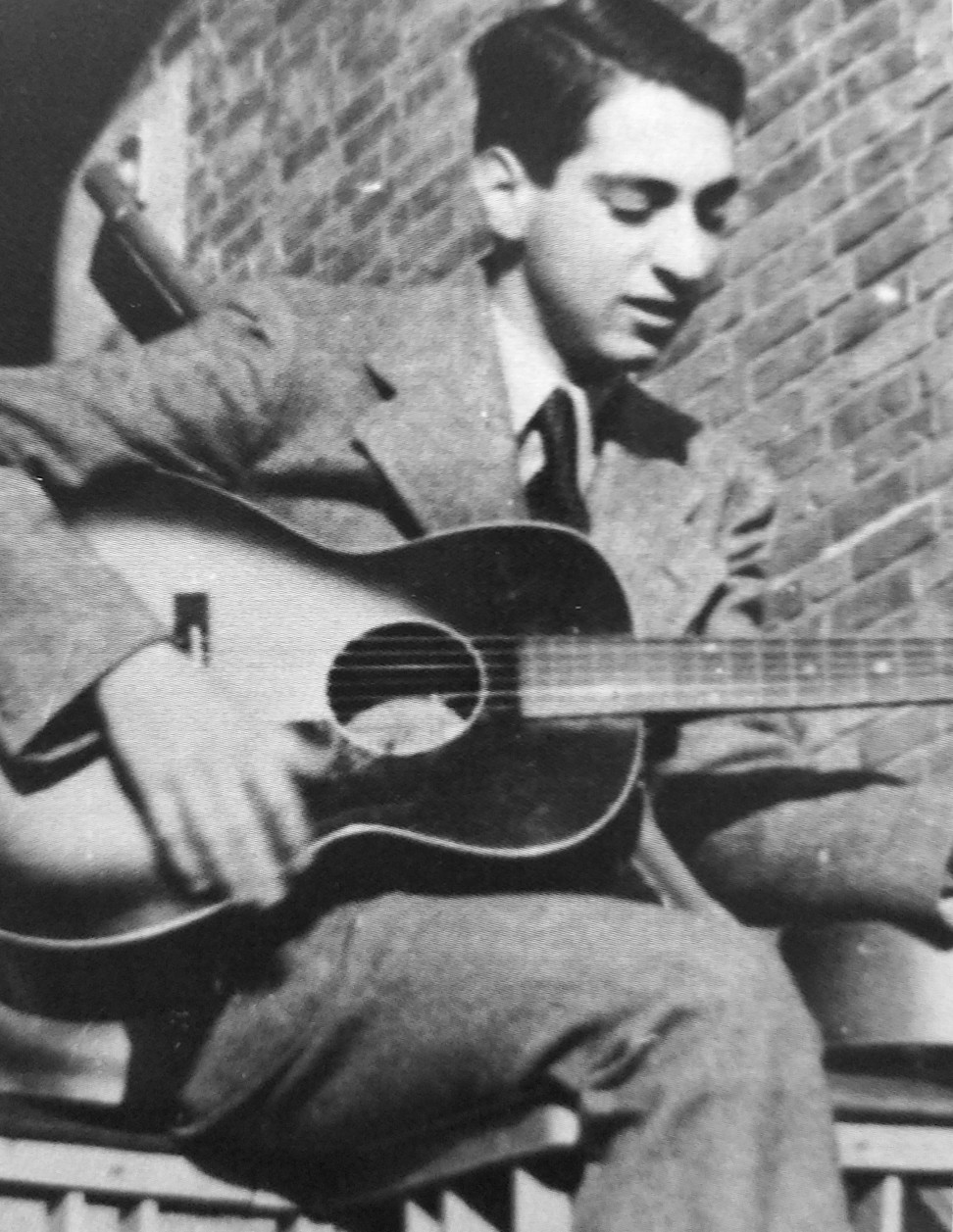

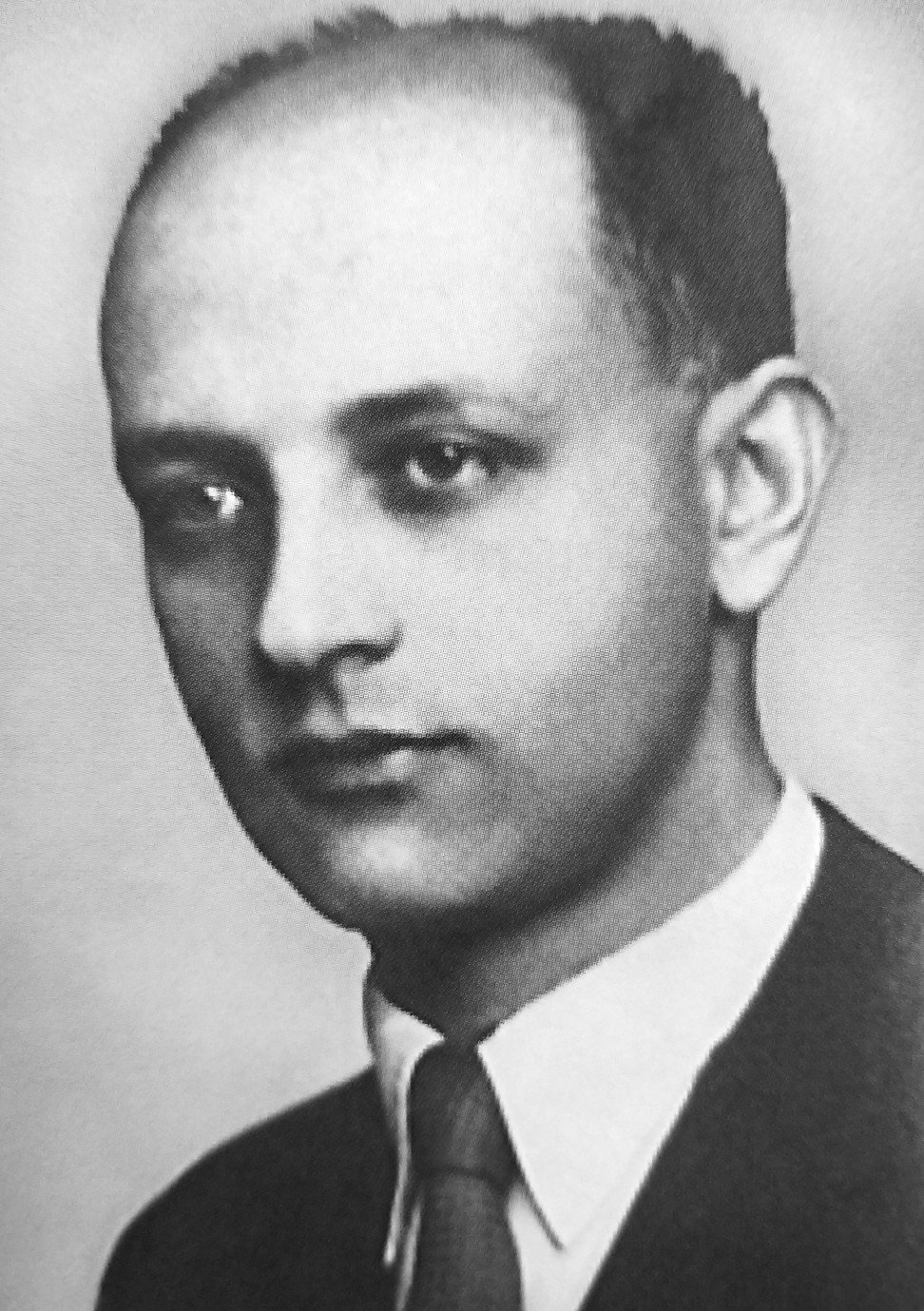

Nazi invasion: I was born in Vienna, into a young family. My father was 21 when he married my mother, who was 18. They had their first child, Heinz, in 1926 and I was born in 1929. My brother and I were quite different – I was a real tomboy and he was calmer and quieter.

In winter we went skiing and in summer we had relatives who owned a spa bath near Vienna where we went at weekends. We were Jewish, but not particularly religious. My parents had Christian friends and went drinking in the evening with them. It was a wonderful life, but it didn’t last, because in 1938 Hitler marched into Austria.

Soon after the Nazis arrived my brother came home from school badly beaten, blood streaming from his face. He said his school friends had done it and the teachers watched and did nothing. My father hatched a plan: he had inherited a shoe factory from his father and was exporting shoes to the south of Holland. He would go there and as soon as he found accommodation would send for us. But within a couple of weeks the borders were closed. Jewish people were attacked in the streets, it wasn’t safe, and I had to leave school.

Meeting Anne Frank: My mother, brother and I went to Belgium illegally – by train and on foot. I was 10 and didn’t realise the danger we were in. My father arranged for us to stay in a boarding house. I went to a Belgian school. I didn’t understand a word of French. At playtime the children stared at me, it was awful. I became shy and miserable, I felt I didn’t belong.

A yellow star: In May, the Nazis invaded Holland. It was a short five-day war. There were 10,000 casualties and the Dutch government capitulated. We tried to escape to England, but the last boat had left. We were stuck. Slowly, the measures against the Jewish population began.

At first, they were a nuisance – we were not allowed on public transport, but everyone had a bicycle, so that didn’t matter. Then we were not allowed to go to the cinema. The first Disney film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, had just been released. For the non-Jewish children it was all the talk and we Jewish children felt excluded. Then the measures became more difficult: there was a curfew from 8pm to 8am; we could only shop in Jewish shops, which didn’t have a proper supply of food; we had to wear a yellow star.

In June 1942, 10,000 young people including my 16-year-old brother got a letter telling them they would be deported to work in German factories. My father was suspicious – why would they invite them when they’d already deported them? But Dutch parents weren’t as suspicious, and many young Dutch did go. They never reached Germany, they were taken to Mauthausen, a terrible Austrian death camp.

The betrayal: My father told us the family had to split up – no one in the Resistance would take a family of four and if we split up there was a greater chance at least two of us would survive. I was 13 and realised this was a matter of life and death. I became very anxious. We were in hiding for two years. Once a week the Nazis searched houses. The first time they came my heart was beating so fast I thought they would hear it through the partition. You didn’t dare to sleep, neither did the owner of the house where we were sheltering.

We moved six or seven times in two years. In May 1944, my father phoned my mother and said the woman where they were staying was blackmailing them for money. He asked her to ask the Resistance to find another hiding place. A Dutch nurse came forward and said she knew a safe place, so they went there. We moved near them.

On the morning of my 15th birthday we were sitting down to breakfast when there was a knock on the door. Two SS officers and a Dutch policeman stormed in and took my mother and I to the Gestapo headquarters. We were separated and they interrogated me about where I’d been and who had helped us. I was in shock, I went blank and couldn’t speak. They started to beat me, and I became hysterical. When they realised I wouldn’t say anything they threw me in a dark room with my mother, father and brother. It turned out the nurse was a double agent. In a court case after the war, we learned she had betrayed more than 200 people.

An encounter with Dr Mengele: We were put on a train that was meant more for animals than humans. There were 70 to 80 people jammed into each car and so little room we had to take turns to sit. There were two buckets – one with water the other to use as a toilet. Once a day chunks of bread were thrown in, as you might feed wild animals.

After a terrible journey of three or four days the train stopped and the doors opened – there were Nazis and dogs and people in striped trousers and jackets, the uniform of Auschwitz. Men and women were separated and we were told to stand in rows of five. The camp doctor, (Josef) Mengele, made the “first selection”. He was about 40 years old. He didn’t look evil, he looked like an ordinary man. He looked each of us over for a fraction of a second and decided whether you were on this side or that.

In the holding camp a nice person had given my mother a hat and she gave it to me. The hat with its wide brim hid my face and Mengele couldn’t see how young I was. That hat saved my life. Nearly half our transport was taken to the “wrong side”, they were the very young and the old. Then, we were herded into a barrack. They told us to forget we had a name, we would be tattooed with a number and had to respond to that.

I was given the number A5272. We were told to strip naked and our heads were roughly shaved. While this was happening the Nazis – men in their 20s – told us with pleasure that the people we had been separated from had a shower. They laughed loudly, “Ha, if you think it was a shower you are wrong, it was gas.” We could see the chimneys where their bodies were burned and there was the smell of burning flesh.

Camp life: The bunks in the barracks were three tier and more like cages, we slept eight to a cage with no bedding or blankets. Twice a day we were taken to some toilets and once a week we had a shower and were deloused. Breakfast was a mug of liquid and in the evening, you got a chunk of bread.

They told us the water wasn’t clean so not to drink it, but if you worked all day in the heat you were thirsty. I drank from a tap one day and got typhus. Some inmates warned my mother not to take me to the hospital, it was where Mengele did his experiments on people, but my mother thought, “She’ll die anyway without medication.”

As we entered the hospital a miracle happened – my mother ran into her cousin Minni from Prague, they were best friends. Minni’s husband was a skin specialist and worked for the Germans, he’d got her a job working as Mengele’s assistant. In her privileged position she was able to give me medication and sometimes got us extra food.

Death marches: From time to time, after we had a shower, Mengele and a couple of Nazis would be there to do a selection, taking out those they thought were not able to work any more. My mother was one of 40 women selected and told to march out naked to be gassed. I managed to sneak to Minni’s barracks and tell her. Soon after my group was moved to a different part of the camp. I didn’t know what happened to my mother, I assumed she’d been killed. It was winter, I had frostbite on my feet and could hardly walk.

The Nazis knew that Russians were approaching so they started to evacuate the camp, they didn’t want us to be liberated. They marched people to Germany and Austria, marches that later became known as Death Marches because most people perished. Many of the guards left because they didn’t want to be caught by the Russians. One day some Dutch people told me they had seen my mother. Several days later I found her – Minni had hidden her.

Bodies piled high: By January 1945 all the Nazis had gone, taking most of the people with them. There were 500 people left in the women’s camp. Many people had died. We couldn’t bury them because the ground was frozen, so I helped take the bodies outside and pile them up. This was the worst thing I’ve had to do in my life.

For 10 days we lived off scraps of food and hacked ice for water. Some Nazis came back to the camp and marched my mother off with 40 others. I saw her go and thought I’d lost her for good, but a few hours later she returned. She’d thrown herself in the snow and pretended to die. A few days later the Russian army arrived with tanks and horses and cooked a wonderful greasy cabbage soup. We ate and ate, but the food ran straight through us and in the morning lots of people had died because they didn’t have the strength to digest it.

I went to the men’s camp to try and find my father and brother. I didn’t find them, but I came across Otto Frank – he was so thin and ashen I almost didn’t recognise him. I fetched my mother and we lived in Auschwitz for a while and then travelled eastwards by truck to Odesa, in Ukraine. By the time we arrived in May, 1945, the war was finished. A New Zealand troop transport ship took us to Marseilles, and we made our way back to Amsterdam, my mother, Otto and I.

Otto was devastated when he heard his wife and daughters had died. Then my mother got a letter saying both my father and brother had died at the Mauthausen death camp. When I realised I’d never be reunited with my father and brother I became depressed and full of hatred. Otto was a great help to me. He told me that when you are full of hate the people you hate won’t suffer, but you will. He suggested I become a photographer and gave me his Leica camera. I went to London to study as an apprentice in a studio for a year.

Laying ghosts to rest: In London, I met Zvi Schloss, who had come from Israel to study economics. We became friends and six months later he proposed. When Otto came to London, I told him and he said that he and my mother had fallen in love as well and when I was settled they planned to marry. So, in 1952 we went to Amsterdam and got married.

My mother and Otto married the following year and moved to Switzerland. They were married for 27 years and I’ve never seen a happier marriage, they really understood each other. They worked together replying to the thousands of letters Otto received after Anne’s diary was published. Zvi and I were married for 63 years, he passed away in 2016.

In 1986, I attended an exhibition for Anne Frank in London and the organiser asked if I would speak. There was a crowd of 200 people and I was very shy. I’d never spoken to anyone about my experiences, not even my husband, although he knew about it. Until then I’d had nightmares, but once I started speaking out about what happened the nightmares stopped. I have continued to share my story since that day.

The Hong Kong Holocaust and Tolerance Centre brought Eva Schloss to Hong Kong for an event at the Asia Society to mark the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Auschwitz.