WWF’s Andy Cornish is trying to save endangered shark species, before it is too late

- Hong Kong is the epicentre of the global shark fin trade and accounts for about 40 per cent of the market

- Cornish, who grew up ‘chasing snakes’ in the city, is working to recover critically endangered shark and ray populations

Wild child: I was born in Chertsey, in Surrey, in the UK, in 1970, and my younger brother was born a year later. When I was two, my dad, who was an engineer, took a two-year contract at Hong Kong University and we moved to Hong Kong. My father had grown up in Baghdad and Taiwan because his father was in the diplomatic corps and he enjoyed being outside the UK. My mum was enthusiastic about exploring Hong Kong and we’d go on little ferries to the islands.

We grew up in High West, the university accommodation next to Pok Fu Lam Reservoir, and my brother and I spent our time after school chasing snakes and swimming and fishing in the reservoir. We were both obsessed with animals and had all kinds of weird and wonderful pets.

I had three fish tanks in my bedroom for years and remember my brother bringing home a rat snake that he’d found at the reservoir. He released it on the balcony where it zoomed around and threatened to bite anyone who went near it – our parents were amazingly tolerant. I went to Kennedy Road School – there was a rising sun above the playground that was left over from the Japanese occupation – and then to Island School.

More the merrier: Our family went to Union Church on Sundays. The caretaker of the church was a Vietnamese lady who had escaped the Vietnam war. She had some issues, so social services took her children away – two daughters and a son. My parents offered to look after the children until their mother was better. So, the three children moved into our house – the first daughter is a year older than me, my second sister about my age, and the brother eight years younger than me.

Many years later, when I was 16, it became clear that the issues with the mother weren’t going to go away, so my parents formally adopted the children. After my A-levels, I took a gap year and went with Operation Raleigh to Cameroon and spent three months living rough in the rainforest. We built a 100-metre suspension bridge into Korup National Park, supported health workers in the local villages, and camped and moved around doing snake and moth surveys.

Everyone lost a lot of weight, a third of the group got malaria and most people got river blindness, including me. I spent a week at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, where I was treated with an experimental drug to kill these microscopic worms crawling under my skin.

Shark scare: Because of my love of animals, I decided to study zoology and went to the University of Nottingham. When I graduated, in 1991, the UK was in recession and I worked in the wholesale supermarket Cash and Carry for two years and saved up money to go backpacking around Central America with a friend.

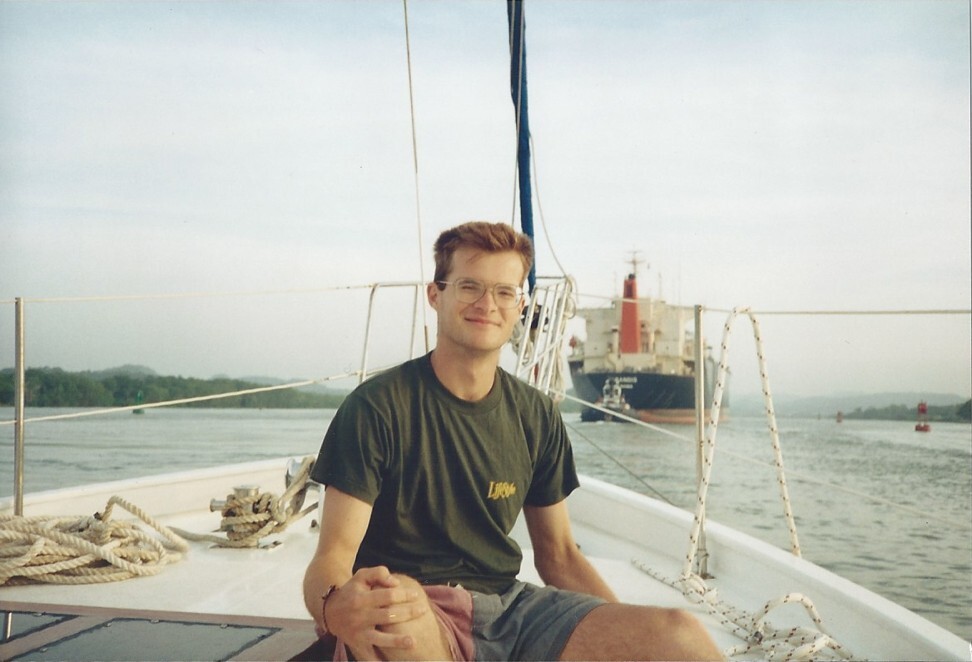

We flew into Costa Rica, went down to Panama, managed to blag our way onto a yacht and went up the Panama Canal. Then we hitchhiked through Nicaragua and El Salvador. We met a couple of guys who said the Bay Islands in Honduras was where you could learn to scuba-dive for US$100. Eventually we got there and learned to dive in fabulous, clear waters.

After another stint at the Cash and Carry, in 1995, I persuaded my girlfriend to come to Hong Kong with me. We lived in a three-storey village house in Shek Kong, in the New Territories. A friend spotted an ad in the newspaper for two fully-funded PhDs – one to study coral fish and the other to study the corals in Hong Kong. Diving was a requirement.

In the middle of nowhere: After I finished the PhD, I set up a company doing underwater surveys of fish and corals for environmental consultancies. It was well-paid work, but the jobs were few and far between, so after a year I began applying for other jobs. I landed one in American Samoa in 2001, overseeing the coral reef conservation projects there.

American Samoa is way out there in the Pacific Ocean, the buses stop running after 5pm and after work I’d go snorkelling with the sharks and turtles. I soon found out that everyone was on island time and if I wanted to get anything done, I had to work twice as hard as I might otherwise do.

I went fishing with friends for yellowfin tuna and we saw pilot whales swim past and jumped in the water to snorkel alongside them. A highlight was when the big coral reef research centre in Hawaii, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said they were sending a research vessel to American Samoa. I joined and spent three weeks on the vessel visiting some of the most remote atolls in the world.

At Swains Island, there were just five people living on the atoll and we exchanged ice cream and alcohol for lobster and a big coconut crab. It was a great experience, but as a young, single guy it was too quiet for me. I came back to Hong Kong and taught at HKU’s Department of Ecology and Biodiversity for three years.

We did a survey recently that found that seven out of 10 people had consumed shark fin in the past 12 months. Globally, the number of shark and ray species that are critically endangered has gone up from 27 five years ago to 43 now, and it’s all about overfishing. One of the big things I’ve been working on is finding out how to recover the shark populations that are doing very badly. So many species are in trouble, so we’re trying to think about ways to recover them before it’s too late.

Natural habitat: I got married in 2015. My wife, Nissa, works for the environmental charity Redress. We have a son who is almost three. In March last year, we moved from Tin Hau to Mui Wo, on Lantau Island, and it’s wonderful to be surrounded by nature – water buffaloes walk past in the middle of the night, and there is an empty paddy field outside with god knows how many species of frog and the chorus is deafening. My son can point out grasshoppers, praying mantis and butterflies. It reminds me of how I grew up in Pok Fu Lam, being able to spend hours and hours with a bucket and sand.

Sharks have been around for 400 million years, but they have been dropping off a cliff in the past 50 years and if we don’t turn things around drastically, species are going to go extinct.