Getting to the roots of Rodrigo Duterte: biographer on Philippine president’s puzzling past

- Why does Duterte dislike the Catholic Church? How did the privileged son of a provincial oligarch develop his rough-edged gangster charm?

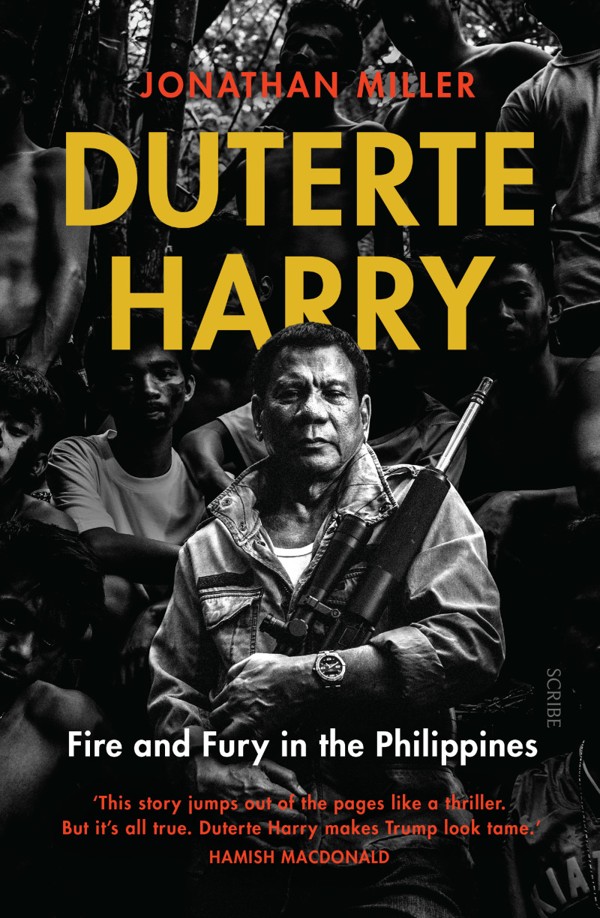

- Duterte Harry author on his fascination with Philippines’ authoritarian leader

A personality appraisal prepared by a psychologist during the annulment of Rodrigo Duterte’s 27-year marriage in 1998 was one of the unexpected gems uncovered as journalist Jonathan Miller researched the background of the president of the Philippines.

Speaking at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival, Miller said the report described Duterte as suffering from a narcissistic personality disorder with aggressive features.

Trainspotting author among Hong Kong literary festival must-sees

“The psychologist referred to his gross indifference, insensitivity, manipulative behaviour, grandiose sense of self and entitlement and concluded that his personality disturbance was serious and incurable,” said Miller, Channel 4’s Asia Correspondent based in Bangkok and author of Duterte Harry: Fire and Fury in the Philippines.

Miller’s book, released in May this year, includes interviews with Duterte, two of his sisters, his daughter, son, old friends, members of his death squads and relatives of his victims.

“Having written this book and dug into his past and seen how he behaves now, [the personality appraisal] struck a chord,” Miller said at the event on Saturday.

While on assignment for Channel 4, Miller attended a hastily called press conference by the then Mayor of Davao, a city in the southern Philippines. After keeping the assembled press pack waiting for three hours, Duterte arrived at 1am and spoke for two hours before opening the event up to questions.

The only foreign correspondent in the room, Miller asked Duterte about human rights and the death squads assembled to kill people he considered undesirable. The question wasn’t well received.

“Duterte conferred on me a Filipino term which translates as ‘You son of a whore’. To some degree it’s a badge of honour, up there with the Pope and Obama who have also been given this badge of honour,” said Miller.

The exchange was posted on YouTube, and by the following morning it had been viewed more than 13 million times. Miller was hooked. Initially it was the sheer number of people killed in Duterte’s death squads that drew him to the story. Having grown up in Northern Ireland, he compares what has happened in the Philippines to “the Troubles” in the British province which claimed the lives of 3,000 people over 30 years.

“In the space of 18 months, Duterte killed three times as many,” said Miller.

We have all read the news stories of the shocking slayings of drug addicts ordered by Duterte, but what many of us haven’t heard about – and what makes Miller’s biography so fascinating – is the back story of Duterte, now aged 73.

The Philippine leader’s dislike of the Catholic Church is well known. Where does it come from? Miller says it’s partly due to Duterte’s beef about corruption in the church, but also because – as Duterte has claimed – he was abused by a Catholic priest in high school.

Miller followed up the story and discovered that the priest Duterte claims molested him, the late Father Mark Falvey, had retired to Los Angeles in the 1980s. He discovered that a year before the priest died the church paid out well over US$1 million in compensation to alleged victims of child abuse to stop the case going to court.

There was another key influence in Duterte’s young life: his mother, a strict disciplinarian. Whenever the young Duterte needed to be disciplined, his mother was the enforcer. “She would make him kneel down on mung beans in front of a crucifix with his arms outstretched. All this had an enormous effect on him,” said Miller.

Miller interviewed one of Duterte’s sisters just after she’d heard her brother railing and ranting at the police. She said Duterte sounded just like his mother. It’s little details like this that makes Miller’s portrait of the brutal authoritarian so fascinating.

So what did the young Duterte do for fun? It seems he hung out with his bodyguard and his bodyguard’s friends, drinking beer and playing with guns. It was there that he picked up the misogynistic attitudes and behaviour that he’s well known for, as well as the rough-edged gangster charm that has so endeared him to the regular folk of the Philippines.

“This rough language appealed to people, but it was based on a lie – he’s a provincial oligarch. His dad had been a member of the Marcos cabinet. He one of the most privileged kids ever to grow up on the island of Mindanao,” said Miller.

There is no living memory among the majority of Filipinos of the miseries of dictatorship and a repressive regime

The most tragic tale of the evening involved Domingo, a pedicab driver living in a Manila slum. Struggling to feed his young family, he would take a few hits of shabu (crystal meth) so he could work longer hours. Domingo bought into Duterte’s talk and voted for him. When he was informed on by his dealer, Domingo signed the drug register and was told that would help him get into rehab. He had inadvertently put himself on one of Duterte’s infamous death lists. Within few weeks later he was dead.

“A gun was fired through the gap in the wooden wall where his family was sleeping. The first bullet killed his six-year-old son. The second bullet killed him. His wife and other children watched. There have been a lot of children killed in Duterte’s war on drugs. Duterte actually called them ‘collateral damage’,” said Miller.

Miller struggles to find anything positive to say about Duterte, but he is acutely aware that the charismatic leader has a huge support base and says they’ve been vocal in their criticism of his views. But if Duterte is an aggressive narcissist, why does he have so many supporters?

“Most Filipinos are too young to remember what it was like to live under Marcos. There is no living memory among the majority of Filipinos of the miseries of dictatorship and a repressive regime,” said Miller.