Witnesses to anarchy

— April 23, 2017It was the bloodiest violence the city had seen: the riots would leave 51 people dead and hundreds more injured. We talk to some of the people involved to make sense of events that forever changed Hong Kong

Fifty-one people killed and more than 800 injured. More than 8,000 “bombs” detonated (most in controlled explosions), of which as many as 1,100 were real. These are figures that will be echoed in the coming weeks as Hong Kong marks 50 years since the start of the biggest and most violent mass disturbances in the city’s history.

But it’s not until you speak to those who lived through the riots of May to December 1967 that you begin to see past the numbers and understand the profound ways in which that chaotic period shaped the city and the identity of its people.

Hong Kong was a very different place half a century ago. Many of its people were refugees from the turmoil then engulfing China, who made their homes in squalid squatter camps.

“The hillsides were covered in shantytowns where they had no running water or toilets,” recalls James Elms, a police inspector at the time. “Jobs were few and employers could pick and choose who they wanted. It was hell, but somehow people survived. This was fertile ground to nurture a spirit of dissatisfaction.”

By early 1967, the impact of the Cultural Revolution, which had begun in China in the middle of the previous year, was being felt in Hong Kong. Factory workers were fired with a sense of injustice. Pro-communist riots had erupted in Macau the previous December and in May 1967, the escalation of a labour dispute at an artificial-flower factory in San Po Kong, Kowloon, marked the beginning of clashes that would shake Hong Kong to its core.

“At the beginning I was quite sympathetic to the workers because we were all from poor families, we all understood the social disparity of the time and how serious it was,” says Ching Cheong, The Straits Times’ chief China correspondent who was, in 1967, a Form Four student at St Paul’s College in Bonham Road on Hong Kong Island. (Two forms above him at the school was Tsang Tak-sing, who would be expelled and jailed for distributing pro-communist leaflets, before becoming a deputy to the National People’s Congress and, in 2007, Hong Kong’s secretary for home affairs.)

“At the beginning I was quite sympathetic to the workers because we were all from poor families, we all understood the social disparity of the time and how serious it was,” says Ching Cheong, The Straits Times’ chief China correspondent who was, in 1967, a Form Four student at St Paul’s College in Bonham Road on Hong Kong Island. (Two forms above him at the school was Tsang Tak-sing, who would be expelled and jailed for distributing pro-communist leaflets, before becoming a deputy to the National People’s Congress and, in 2007, Hong Kong’s secretary for home affairs.)

Elms – whose mother was Chinese and father English – was living in North Point and working nearby, at the Bay View Police Station, at the junction of Electric and Watson roads. He was at home asleep at 1pm on May 6 when trouble flared at the Hongkong Artificial Flower Works’ San Po Kong factory, where striking workers disgruntled over wages and the recent dismissal of 29 machine operators had been locked out. He was ordered to return to the station, where he would be on standby should trouble spread across the harbour

The following day he was deployed to San Po Kong. He recalls union leaders coming out of the factory to make their demands and that the crowds then dispersed, but May 11 was not so peaceful.

“The police were there in strength and there was counter-attacking – there was tear smoke [tear gas] fired and baton charges. And then the trouble spread to Wong Tai Sin, to East Kowloon and predominantly Shek Kip Mei,” says Elms. Beneath the front-page headline “Disturbances at Sanpokong”, the May 12 issue of the South China Morning Post reported that “Just 13 months after last year’s [Star Ferry] riots, part of Kowloon was once more under curfew order last night following clashes between steel-helmeted riot police and mobs of both workers and teenagers.”

Resentment continued to simmer and boil over throughout the summer but, after the initial strikes and demonstrations, Ching says, he began to realise that political issues were at the heart of the labour movement. And then things turned nasty.

“What I want to stress is that I began not to support the labour movement once it resorted to blatant violence by planting bombs all over the place. That was urban terrorism – it is an accurate term to describe the situation in the second half of 1967,” says Ching. “The left-wing labour movement turned into a terrorist movement.”

Also a student at the time, Joseph Cheng Yu-shek, who would go on to become a pro-democracy academic and convener of the Alliance for True Democracy, recalls the fear among Hong Kong people as the violence escalated. “People, of course, were worried and, as a school child, one can remember your rich classmates leaving Hong Kong. The rich families sent their children to study in the US or England. But there was only a small number of rich families; most of us were quite helpless,” he says.

Gary Harilela, vice-chairman of Harilela Hotels, was 30 years old at the time. He and his four brothers were running a tailoring business in Tsim Sha Tsui. His children were young and he was concerned for their safety. “It was very anti-foreigner,” he says. “As foreigners we didn’t know what the outcome would be.”

In early May, one of his Chinese staff tipped him off that trouble was brewing, says Harilela. He and his brothers locked up the shop and left as quickly as possible. On the advice of their staff, they put a Chinese flag up against the windscreen of their car. Turning off Nathan Road into Waterloo Road, they came across a large crowd of rioters. Harilela believes the flag helped them get through the angry mob unscathed.

Back in Kowloon Tong, neighbours were selling up as they prepared to flee Hong Kong.

“Dr Gunten was a Portuguese doctor living four or five houses away from us,” says Harilela. “He put his house up for sale – a 10,000 sq ft house. He was asking HK$5 million, but he ended up selling it cheap, for just HK$1.5 million. That was a chance we missed. He sold up and went to Canada.”

Elms recalls the atmosphere in his North Point neighbourhood. “There were plenty of people from Fukien [Fujian province] and they predominantly supported the leftists. They were housed in a block called Kiu Kwan Mansion, which is opposite the Metropole. At the bottom of Kiu Kwan Mansion was Wah Fung Chinese Products – otherwise known as the base of operations for everything as far as the left went.”

Entering Wah Fung Chinese Products “was no different from walking into the Cultural Revolution – everybody there wore white shirts and grey trousers and had Mao Zedong badges on. Every time [the leftists] came out and did things; when the police arrived they disappeared into the building, so take a wild guess – something must be going on in there,” says Elms.

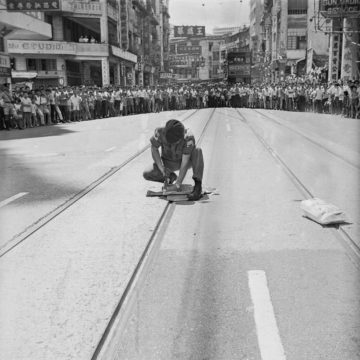

Home-made bombs were a defining feature of the troubles as they continued to convulse the city. Many were fake, but enough were real to spread panic.

“It was a little bit funny looking back then because the bombs had signs,” says Cheng. “You saw an object like a tin can or a shoebox with a sign on it saying, ‘This is a bomb – stay away.’ People would cross the street to avoid it.”

You came across them regularly, recalls David Akers-Jones, then a civil servant working in Yuen Long with an office in north Kowloon.

“The packet, the bomb, would be in the middle of the road and we would drive astride the bomb, one wheel on either side. It wasn’t very pleasant,” says Akers-Jones, who would go on to become the government’s chief secretary for administration and served as acting governor of Hong Kong between 1986 and1987. He remembers the bombs as being “rather amateurish” – they were usually made from firecrackers, he says, which led to a ban.

“Now we have paper […] firecrackers in Hong Kong,” he says. “People don’t realise why they are like that, but it was because in the Cultural Revolution they were full of gunpowder, which could be used in the making of small bombs.”

Some left-wing schools were involved in the bomb making, Ching recalls.

“In secondary school science lessons, they asked the students to manufacture bombs in their labs,” he says. “Obviously, accidents happened in this situation. In one of these schools, a major explosion blasted off the arms of a student [in November 1967].”

Chung Hwa Middle School, in Peel Street, Central district, was closed by the government following the accident, in which 18-year-old Siu Wai-man lost his left hand. The closure was intended to be temporary, until August the following year, but governor David Trench pushed to have the school deregistered.

“I do object very strongly to the uncontrolled spread of a communist school system which is merely a deliberate breeding ground for hate and violence,” Trench wrote in a telegram to the Commonwealth Office. Chung Hwa Middle School would not reopen.

On the day after the explosion, police raided four other communist-run schools suspected of being bomb-making facilities – the Mongkok Workers’ Children School; the Heung To Middle School, in Shek Kip Mei; Western’s Hon Wah Middle School; and Fukien Middle School, also in Western.

Harilela recalls returning to his Kowloon Tong house with his children one Sunday afternoon to find a parcel outside the front gate. There was no sign attached to it. He took his children to safety inside the house and called the police.

“From my mother’s room that faced out onto Waterloo Road, I watched the police slowly move the parcel into the centre of the road and then I heard a loud bang,” says Harilela. “The bomb would have gone off if someone had picked it up.”

Others were not so fortunate. On August 20, two children – eight-year-old Wong Yee-man and her two-year-old brother, Wong Siu-fan – were playing not far from their North Point home when they found a parcel near Kiangsu-Chekiang College. They picked it up and were carrying it home when the bomb went off. Hearing the explosion, their father came running out to find his daughter dead, a deep hole in her stomach, and his son covered in blood and soot. Siu-fan died in the ambulance on the way to hospital.

Commercial Radio host Lam Bun, who was known for his criticism of leftist extremism, was burned alive on August 24, when he and a cousin were driving from their flat in Waterloo Road to work. Two hitmen pretending to be road-repair workers stopped the car and tossed a petrol bomb through the window. As the two occupants staggered out of the burning car, the assassins poured petrol over them and set them alight. Lam died the following day and his cousin five days later.

The killings struck fear into the hearts of the Hong Kong people and turned them against the leftists.

Akers-Jones was closely involved with one of 1967’s most violent episodes – the killing of five policemen in the border village of Sha Tau Kok on July 8. Eleven more were injured. Two years ago, the Hong Kong Police website controversially revised its account of this incident, deleting a reference to communist militia and suggesting the attack had been carried out by “gunmen” whose identity was unclear.

Akers-Jones says: “A number of police officers were killed when the militia attacked the police station from across the border.”

According to a report in the July 9 edition of the South China Sunday Post-Herald, “More than 300 armed Chinese militia and demonstrators trapped 86 policemen in the Shataukok rural committee building and police outpost within the two-mile restricted border area for nearly 10 hours.”

Corporal Fung Yin-ping and constables Kong Shing-kai, Mohamed Nawaz Malik, Khurshid Ahmed and Wong Loi-hing lost their lives before about 500 British Army Gurkha soldiers moved in to break the siege.

“The attack on the police station and the killing of the […] policemen marked a tremendous change in the governance of the New Territories,” says Akers-Jones. Gurkhas, part of the 48th Infantry Brigade at Sek Kong, were stationed in Sha Tau Kok and along the western section of the border. “[There was] nothing but a barbed wire fence between them and mainland China, so it was a very sensitive relationship.”

He recalls farmers singing revolutionary songs and carrying red banners as they crossed into Hong Kong to tend their crops.

On September 29, two off-duty policemen riding a motorbike accidentally crossed the border and were detained. On October 14, senior police inspector Frank Knight went to investigate. According to Gary Cheung Ka-wai, in his book Hong Kong’s Watershed: The 1967 Riots (2009), Knight was “dragged across the border bridge by a group of mainland farmers” after an argument at the border fence. Akers-Jones, who was a friend of the late Knight, prefers the term “hustled”.

The result was that the bridge was barricaded and movement across the border ceased. The farmers seethed as their crops went untended and, on the Hong Kong side, there was anger over the detention of the policemen. Akers-Jones and the government’s assistant political adviser, Kenneth Kinghorn, were brought in to negotiate with Chinese officials. The negotiations began with three readings taken from Mao’s “little red book”.

“We solved it by paying compensation for the crops that were spoiled as a result of the closing of the border and arranged for the return of the policemen together with their accoutrements; pistols and things,” says Akers-Jones.

Hong Kong was reeling by the time the riots finally subsided, in December 1967. What followed was a series of major social reforms, the groundwork for which had already been laid, that would shape the future of the territory

“Elsie Tu, who was a democratic fighter, was part of the review after the 1966 riots and she told the government it had lost communication with the ordinary people of Hong Kong,” says Akers-Jones. “As a result, we opened offices [what would become the District Council offices] for ordinary people on the street so they could communicate their needs.

“The riots had a great effect on the relationship between the people and the government.”

Cheng says the colonial administration realised the importance of listening to the public and, as a result, community ties were strengthened. Then, in 1971, Hong Kong received a new governor.

“Murray MacLehose was proactive in introducing public housing and free education – this responsiveness, this improvement in social services, plus the fact that Hong Kong was enjoying a boom in the late 1960s and 1970s; people were happy,” says Cheng.

Many of those who had fled the Cultural Revolution remained in squatter settlements in Kowloon, in the shadow of Lion Rock, and when RTHK television series Below the Lion Rock began its run in 1972, it brought into focus a period that saw Hong Kong built out of poverty. The theme tune was said to capture the spirit of the city’s people and it is this “Lion Rock spirit” that Ching believes was born during the 1967 riots.

“The Hong Kong nationality was first developed in 1967,” he says. “Before that incident, Hong Kong was a borrowed place on borrowed time but, after the riots, people knew that Hong Kong was their home and that they wouldn’t return to China any more.”

Two other historical events would similarly galvanise Hong Kong, says Ching: the 1989 demonstration against the Tiananmen Square crackdown and the 2014 “umbrella movement”. But it was in the cauldron of the 1967 riots that Hong Kong’s enduring identity was forged.

“After the riots, for the first time, we had a sense of belonging in Hong Kong,” says Ching.

Original Link: SCMP