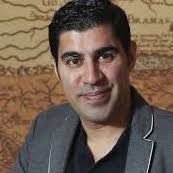

Chris Patten’s Hong Kong aide Kerry McGlynn

— May 19, 2017Australian former journalist Kerry McGlynn, the man behind Hong Kong’s branding as Asia’s World City, recalls the last British governor’s ‘amazing’ sense of humour and how the ‘heavens wept’ when Chinese rule resumed

I was born in a town in the Riverina district of New South Wales called Leeton. When we went to Sydney, just before I started school, my father took a job as a box maker and then became a butcher. I went to an Irish Brothers school called St James. I made just one term of high school – I was a 15-year-old dropout.

After an unsuccessful stint at a timber factory in working-class Glebe, my mother spotted an ad in the Daily Mirror for a copy boy. I applied and got it. They put me in the sub-editors’ room, where I used to shoot the copy into the composing room. After a year or so I worked in the police rounds rooms, ringing around the police, ambulance and fire stations finding out what was happening. I got accepted for a cadetship for my 17th birthday.

I only did 18 months of a four-year cadetship. It was an era when journalism was expanding and there were opportunities. In 1963, myself and a journalist mate and photographer went to England. I worked in the Murdoch bureau, just off Fleet Street, and then for the Australian Consolidated Press.

I met my beautiful wife, Jenny, on a trip down to Bournemouth. We were married in Hampshire in 1965 and went back to Sydney in 1968. Because I’d been working in the Packer bureau in London, I resumed my career on the Sydney Daily Herald and Sunday Telegraph, mainly as a feature writer.

In 1974, I saw an advertisement for senior information officer with the administration in Hong Kong, applied and landed the job. My first job was in the Labour Department. After all those years in journalism, I found it difficult moving over to the “dark side”; it took a few years to get comfortable with it. I am settled on a philosophy that journalism and PR are two sides of the same coin.

In 1974, I saw an advertisement for senior information officer with the administration in Hong Kong, applied and landed the job. My first job was in the Labour Department. After all those years in journalism, I found it difficult moving over to the “dark side”; it took a few years to get comfortable with it. I am settled on a philosophy that journalism and PR are two sides of the same coin.

After 2½ years in the Labour Department I worked for several years in the New Territories Administration under David Akers-Jones. It was an exciting time in Hong Kong’s development – we were building new towns in Sha Tin, Yuen Long and Tuen Mun. Murray MacLehose was governor; he was very dynamic.

In 1980 – after MacLehose had been into China and met Deng Xiaoping – they expanded the (Hong Kong government office in) London to increase Hong Kong’s profile in preparation for the handover negotiations. I went to the London office with Jenny and our two kids, Kate and Lucy.

I came back to Hong Kong in September 1982, at about the same time that Mrs Thatcher fell down the steps at the Great Hall of the People, but those of us who had been sent to London weren’t aware of that because it was kept deeply and darkly secret. In 1987, I went to New York for four years; I was director of the (Hong Kong government) office there. I enjoyed every millisecond of it, working with a small but influential group of people who had interests in Hong Kong.

Though my tenure there included the June 4 massacre, Americans had a practical down-to-earth view that Hong Kong probably would be fine.

I came back to Hong Kong just in time to see Chris Patten appointed as governor. I was watching a TV interview he gave from London and I said to Jenny, “I’m going to work for this guy.” Patten was such a breath of fresh air. He was the first governor to have a pressman. In the first week I was there I went on a trip to Japan with Patten and on the way back he got me to sit next to him and told me the sort of things he’d expect of someone who was working for him as a spokesman. He said, “You’ve got to know everything I know, not necessarily because you need to know what to say but because you need to know what not to say.”

I came back to Hong Kong just in time to see Chris Patten appointed as governor. I was watching a TV interview he gave from London and I said to Jenny, “I’m going to work for this guy.” Patten was such a breath of fresh air. He was the first governor to have a pressman. In the first week I was there I went on a trip to Japan with Patten and on the way back he got me to sit next to him and told me the sort of things he’d expect of someone who was working for him as a spokesman. He said, “You’ve got to know everything I know, not necessarily because you need to know what to say but because you need to know what not to say.”

I would sit in when he was talking to (then British prime minister) John Major or (foreign secretary) Douglas Hurd or any other foreign ministers. I got a pretty good ear for the way Chris spoke. Often I wouldn’t need to actually consult him because I knew pretty well everything he was saying or thinking.

One night I was at Government House, standing in the drawing room, and Patten’s daughter, Alice, tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Dad”. And then reeled back and looked at me. I used to joke that I could be Chris’ stand-in any time he was unpopular.

Chris has an amazing sense of humour. One time I was with him when he went to meet Michael Howard, the British home secretary, about getting passports for the war widows who didn’t have British nationality. Patten introduced us all to Michael and when he got to me, he said, “And this is the Australian ambassador.” Michael looked at me quizzically and shook my hand and I said, “But only during the cricket season, Home Secretary.”

On the night of the very British – it didn’t stop raining – handover, I was at the Convention and Exhibition Centre afterwards and Patten’s political adviser, Bob Peirce, said to me, “If you’re talking to the journalists, why not tell them there’s an old Chinese saying that when a great man leaves, the heavens weep.” I said, “That’s fantastic, who was the Chinese philosopher?” “Never mind,” he said. I rang a circle of journalist friends including the BBC, RTHK and AFP and this quote got publicised.

After the handover I worked closely as a speechwriter for [the Hong Kong government’s No 2 official] Anson Chan and [her successor and later chief executive – the head of the city goverment] Donald Tsang. During the Asian financial crisis I was the key player in government who drove the idea of branding Hong Kong as Asia’s World City – it originally came to me from Peter Sutch, (then chairman of) Cathay Pacific.

Jenny became pretty ill and we went back to Australia in 2002 and she passed away in 2004. She helped found LEAP [Life Education Activity Programme] and I like to think of that as her legacy to Hong Kong; it has helped thousands of children.

In 2005, I got a call from government people asking me to come back to do the PR for the World Trade Organisation. And while I was there, Philip Chen, who was then the chief executive of Cathay, offered me a job on a one-year contract that lasted about 6½ years. I loved working for Cathay. I learned a lot about aviation. It’s an action industry so there’s always something in the press, good or bad. There were pictures of a cabin attendant giving a b***job to one of our pilots that went viral and were embarrassing for the airline because it looked as though they might be on duty. We had to handle that fairly sensitively.

I love journalism, newspapers and being with journalists because they’ve always got something to say and interesting experiences. From all my years as a journalist I never got the ink out of my blood. I went back to Sydney on October 31 last year. At my farewell dinner (in Hong Kong) there was a sweep about when I’d be back and the guesses ranged from two weeks to six months. As it turned out, I came back in December to do a job for China Light and Power, with whom I have a retainer.

And, of course, I came back for the (Rugby) Sevens and, while I was here, Cathay asked me to do some work for them. But mostly I’m retired in Sydney and although I never thought I’d say so, I’m quite enjoying life.

Original Link: SCMP