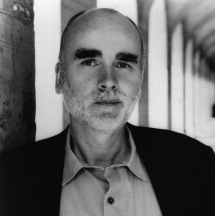

Stephan Elliott on the movie that changed his life

— October 14, 2017The roaring success of the 1994 film was followed by years of bad luck that included a near-fatal skiing accident for its director. As the musical based on the cult classic wows Hong Kong audiences, the filmmaker shows an unusual degree of restraint

Stephan Elliott is learning to keep his mouth shut.

The Australian film director and screenwriter responsible for the 1994 cult classic The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Deserthas earned a reputation for telling it like it is – both on and off screen.

We are in the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, sunlight streaming in through the windows from Lower Albert Road. Elliott’s minder, the affable press director from the Australian consul general’s office, has taken the hint and shifted to the other side of the bar.

Elliott is fresh off the plane from Sydney and drinking his tea strong – double bags. He’s excited about the coming week, which will see a screening of Priscilla (on October 5) and a documentary about the making of the film, Between a Frock and a Hard Place (October 4) – both part of Pink Season HK, Asia’s largest LGBT festival. What’s more, the musical based on the movie has started a four-week run in Hong Kong. And soon he will be whisked off to the mainland – with his partner, Wil Bevolley – courtesy of the Australian consulate in Hong Kong.

“I’ve stopped over in Hong Kong a million times, but they were literally just stopovers,” Elliott says. “When they asked me about this trip I said, ‘Yeah, I’d like to come and explore.’ It’s the first brand new territory in a while – I’m looking forward to being woken up a bit.”

It has been just 10 days since Elliott wrapped up production of his latest movie, Swinging Safari, which is due for release in Australia in January. The comedy-drama, which follows the mayhem that ensues when a blue whale washes up on an Australian beach in the 1970s, is so fresh, he says, he hasn’t had the chance to work out what he wants to say about it, yet.

He starts off cautiously, explaining why the working title – Flammable Children – was dropped. “We found it was scaring quite a few people. A bunch of people asked me if it was a horror film.”

The new title more accurately reflects what happens in the movie; while children in the suburban beach town are excited about the whale, their parents celebrate by throwing a wife-swapping party.

Elliott had the idea 30 years ago but decided to sit on it until he felt mature enough to write the script, with enough distance from his own childhood. That time has come – he’s ripped off the rose-tinted glasses and taken a long, hard, and funny look at what it was like growing up beside the beach in the late 70s.

“I collected all the childhood memories – many of my own, many of other people’s, of friends. We’re calling it ‘the sand which time and taste forgot,’” he says.

He scoured his family photos and asked the cast to bring in theirs.

“A lot of us grew up with what we thought the 70s looked like, but the 70s in Australia were actually kind of messy,” he says. “Bad terry towelling hats, nothing matched – you think it was the stylised look of the 70s and it was a complete mess.”

General behaviour wasn’t that smart, either.

“We would get home sometimes missing a tooth or bitten by a snake or fried [by the sun]. The adults were p***ed,” Elliott recalls. “No one said, ‘Where were you? You’ve been bad.’”

Changes in social mores – you can no longer smoke or drink on the sand, for instance – mean Australia’s beaches are cleaner, he concedes, but some things have been taken a step too far. You need a licence to play with a ball on Sydney’s Bondi Beach, for instance.

“[The new film] is fun, it’s not finger-pointing. I found a way of being a little bit un-PC. Little things like sticking a cigarette in a kid’s mouth, lighting it, making them smoke it and saying, ‘Toughen up.’ I’m fully expecting the censors in one or two countries will make us pull bits,” Elliott says.

He’s prepared his defence – it’s not a contemporary film, it’s about what happened in the 70s. And wife swapping happened in the 70s. So, if this is drawn from his childhood, were his parents swingers?

“I’ve asked them outright and they said no,” Elliott says, taking the question in his stride. “And I’ve asked everyone else and they all said no as well but, unfortunately, I know that not to be the case.”

Intriguing. How so?

“I saw a couple of things that I shouldn’t have seen. I’d say, ‘Well, what was that?’ And they’d say that was … ” Elliott’s voice trails off.

This is a movie based on collective childhoods but the storyline is drawn from what happened to a family in his neighbourhood. He hints at scandal – “these people have conveniently moved on” – but we are going to have to wait for the film to find out what that was, exactly. And then he’s back to talking about how un-politically correct things were and how Australia got the sexual revolution wrong.

“By the time the sexual revolution hit Australia it was already literally out of date and they got all the rules wrong,” he says. “Australia was a long way away – I often say it’s like Chinese whispers, by the time it got there it had all got a bit confused.”

Wasn’t the sexual revolution all about freedom and self-expression, not having rules? How can you get that wrong? Elliott relents and gives an example from the film.

The suburban mums and dads had heard about wife swapping and that car keys were exchanged, but they hadn’t got the memo about the keys being placed in a salad bowl and instead used a vase. And yes, you got it – one of the women gets her hand stuck in the vase. A classic Elliott sight gag.

“It plays very much on getting the rules wrong,” he says. “The vibe [the film] takes more than anything else is completely anti-political correctness.”

This attitude is nothing new to Elliott; he’s known for putting his foot in it and admits to thriving on saying the wrong thing.

In The Lavender Bus, producer Al Clark’s 1999 memoir about the making of Priscilla, he recalls how the film’s Cannes premiere was almost wrecked when, upon being introduced to a fellow director, Elliott bellowed, “Of course I know him – I used to bonk his wife!”

Elliott got down on his knees before the couple the following day, one of many apologies he gave – or should have given – in the giddy aftermath of Priscilla’s success.

“I’ve got into too much trouble over the years because I will say exactly what I think and cause a lot of trouble for other people. But finally, at the grand old age of 50, I’ve learned to filter it a bit more,” says Elliott, who is 53.

Fortunately, the filter isn’t 100 per cent foolproof and enough of the “old” Elliott seeps out – sometimes sharp, often sensitive, and dark and funny in equal measure. And even though he’s “learned to put a sock in it”, he doesn’t hold back when it comes to the script.

“When I’m on my own and putting it on paper it just roars out,” he says.

Snappy lines are Elliott’s forte. Priscilla was released almost 25 years ago, but fans of the epic road movie, in which three drag queens drive from Sydney to Alice Springs in a bus, can recite by heart many of its one-liners.

There’s the classic when transsexual Bernadette, played by Terence Stamp, turns to drag queen Felicia (Guy Pearce) and says, deadpan: “That’s just what this country needs: a c**k in a frock on a rock.” It’s Bernadette, too, who delivers the stinging: “One more push, I’m going to smack his face so hard he’ll have to stick his toothbrush up his a*** to clean his teeth!”

Says Elliott, “No matter where I go, particularly in gay worlds around the world, the amount of lines that come back at me without people ever knowing it’s me … It’s kind of creepy in a weird way.”

Swinging Safarireunites many of the Priscilla collaborators. It’s led by Pearce – who well and truly buried the boy-next-door image he earned in soap opera Neighbours with his role as Felicia – and the team includes Oscar-winning costume designer Lizzy Gardiner, production designer Colin Gibson, film editor Sue Blainey and score composer Guy Gross.

“It’s the first time ever I’ve got the whole crew back together, so it’s a reunion,” Elliott says. “Everyone knew about it and had been talking about it for long enough. We are all still thick as thieves – there is a real family there. But it’s a weird moment where we’ve all moved on a bit and there’s four Oscars between them all now.”

Gibson rejoined the team fresh from his Oscars win for Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), for which, Elliott says, he had a budget of US$1 million, compared with the US$100,000 he had to make do with on Swinging Safari.

I tell Elliott that it’s Pearce’s 50th birthday the following day – October 5; I’ve done my homework – and he gasps and starts tapping into his phone.

“Really, 50? I thought he’d been quiet over the last few weeks,” he says. “Oh, he’s not going to be coping, I know that right now. That means Kylie [Minogue] is not far behind.”

He admits to having had a wobbly year in 2014, when he himself hit the half-century, and says he sulked all the way through the party that Bevolley threw for him.

“I didn’t want a party,” Elliott says. “I didn’t like it – I’m a control freak. I’d rather have control over someone else’s party.”

The right side of the big five-oh for another seven months, national treasure Minogue also stars in Swinging Safari, along with other Aussie greats such as Jack Thompson (who makes a cameo appearance as the mayor of the seaside town), Asher Keddie, Radha Mitchell, Julian McMahon and Jeremy Sims.

A galaxy of stars meant Swinging Safari couldn’t be filmed in the same relaxed way that Priscilla was.

“I’d love to say, ‘Come, we own you for the next seven weeks, we are going on a journey together.’ But it doesn’t work that way any more,” Elliott says. “Everyone is going in and out, in different directions.”

There’s no mistaking Elliott for anything but an Australian – the accent, the brash humour and easy laugh – but there are also vestiges of his 17 years in Britain, where he keeps a house in London’s West End. And for all the gaffes and laughs, his current bedside reading hints at a complex personality.

“I’m reading a book at the moment about why we lie and the bottom line is it’s a survival mechanism,” he says, adding that he has to tell the odd fib, now and then. “People management. Sometimes you’ve got to tell people what they want to hear in order to get the most out of them.”

After the huge success of Priscilla came a slump. In 1997, Elliott released Welcome to Woop Woop, a black comedy that was widely panned. He insists it is an amazing film but was shown before it was ready. The Cannes Film Festival asked to take a look at it even though he and the team had spent only four weeks editing the movie, instead of the usual 12.

“The festival said, ‘Apocalypse showed Apocalypse Now as a work in progress, the film wasn’t finished.’ Ego got the better of me and I said, ‘Let’s do it.’ And we were booed out of the Palais [des Festivals et des Congrès],” he says. “I’ve never had tomatoes thrown at me before – it was horrendous and that was the end of that film.”

Wounds licked, he returned with the opaque art-thriller Eye of the Beholder (1999), an attempt at a genre change. There was plenty of drama but it, too, went belly-up.

“I tried to do something that I’d never done before,” he says. “And then I was criticised for it not being funny.”

The bad run of luck concluded with a near-fatal ski accident in the French Alps in 2004 in which Elliott broke his pelvis, legs and back. The slope was so remote the emergency helicopter couldn’t land and when he finally reached the badly haemorrhaging Elliott, the medic didn’t have blood with him. The director was told he had minutes to live and to make his peace.

“I thought, ‘F***, here we go. I’ve had an extraordinary life; I’ve lived like a king; I have nothing to complain about; I’m not going to go out crying or carrying on’ – and this stupid grin broke out across my face and the doctor said, ‘What are you laughing about?’ And I said, ‘Everything.’”

He wasn’t laughing two and a half days later, when he woke up in hospital, in a huge amount of pain. He was too fragile to be moved back to London – where he was living with Bevolley – so he stayed in France to mend. But the process was slow, his French was basic and, with Bevolley visiting for short periods, he felt desperately lonely.

Against medical advice, he booked himself on an air ambulance – “thank god for insurance” – but disaster struck again when the light plane hit a storm over Calais. The plane made an emergency landing but “in the shake-up, everything smashed again – pelvis, back and legs,” he says. “The bleeding had started again, it was going back to scratch, and again they said, ‘You’re not going to make it.’”

He did, of course, but back in London, recovery was slow and Elliott became increasingly frustrated that, despite a second and then third chance at life, he wasn’t feeling like a better person. This was likely down to his predicament: “You can’t walk, you can’t p***, you can’t eat, you can’t s***, you’ve got a bag up your a***,” he says.

He spent several years having to self-catheterise – “you want to go to the toilet but you can’t, and the only way to do it is the old-fashioned way: sticking a large plastic tube up until it hits your bladder” – and walking with a stick. But he pulled through, with a little Priscilla magic. He co-wrote the musical, and the show premiered in Sydney, in October 2006. It has toured all over the world since, from London to Sao Paulo, Athens, Stockholm, Italy, Spain, Tokyo – and now Hong Kong.

In 2008, Elliott released his first film in almost a decade – Easy Virtue, an adaptation of a Noel Coward play. The movie premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, and received a standing ovation. That night, as Elliott and the cast celebrated, the opening shots in a bidding war for the film were being fired, but daybreak would bring bad news.

“We woke up and the stock market crashed, the film industry crashed, the world fell apart and the film fell among the cracks,” Elliott says. “I still call 2008 the year that the whole industry changed, everything changed.”

Nevertheless, Easy Virtue was a success in Australia, the United States and elsewhere, although it didn’t go down well in Britain, where Coward purists didn’t take to it. And 2008 was also the year in which Elliott entered into a civil partnership with Bevolley – a Brazilian architectural designer – in London. The couple had met at the Priscillapremiere in Rio de Janeiro.

“I don’t know how we’ve managed all these years, but we have and it’s just got better and better so I’m very lucky,” Elliott says. “He’s the quiet one in the relationship, the one telling me to shut up.”

Considering that Elliott penned the ultimate camp movie and musical, he’s not overtly camp himself. He’s loud, certainly, but he’s not effete and says he has struggled with his sexuality.

“I’ve been quite reticent about it. I’ve been keeping back, but I’m now getting over myself,” he says.

He’s eager to see how Priscilla, the documentary, which will be shown to select audiences in Shanghai and Guangzhou, is greeted on the mainland.

“I’m going to show the film and see how I go,” says the newly restrained Elliott.

Original Link: SCMP