- Rise programme focuses on bringing women into a safe environment to work through their substance use, and to see what trauma caused it

Growing up in Belfast in the 1970s – in the time of the “Troubles” when there were bombing campaigns and shootings across Northern Ireland – Paula Shields saw a “traumatised generation” around her.

“People were socialised into an active conflict zone, there was segregation, mistrust and fear. The amount of medication handed out without any appointment was unbelievable,” she says.

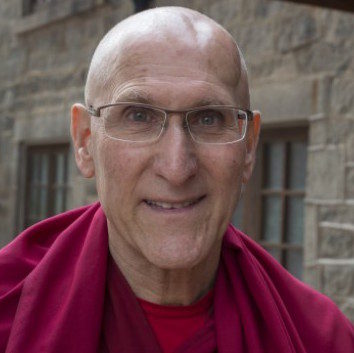

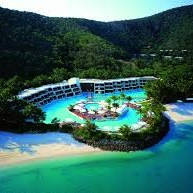

Shields is the clinical lead of the Rise programme, an addiction programme for women with a focus on trauma at The Cabin in Chiang Mai, Thailand. She also played a key role in designing the programme, which is billed as Asia’s first “trauma-informed, gender-responsive women’s programme”.

Why trauma and why women only? Women with trauma often use drugs or alcohol so they don’t have to feel, says Shields. And it is a women-only programme because women’s trauma histories tend to be different from men.

While growing up in a conflict zone or surviving a terrorist attack can result in trauma, it is just as likely to happen in a domestic setting – even more so for women.

Dr Stephanie Covington, a California-based clinician with more than 30 years of experience in designing and implementing treatments for women and girls, says while in childhood boys and girls are both at risk of physical and sexual abuse, by adolescence the risk profiles change.

“In adolescence, men are more at risk of people who dislike them or strangers. If they are gay, young men are at risk from strangers and the police. But women are more at risk within their relationships – the people who say, ‘I love you’,” says Covington.

Noting the relationship between substance use and trauma in women’s lives, Covington devised a treatment model that weaves addiction, trauma and women’s psychological development, called Women’s Integrated Treatment (WIT).

When she first proposed such an idea in the late 1980s it seemed very left field, but today it is widely accepted and Shields has incorporated elements into the Rise programme.

Dr Covington says research shows that women in women-only programmes do better in terms of their recovery from addiction and from mental illness.

“In women-only programmes, women share more deeply and are more open about their lives than if they are in co-ed programmes, where there is more posturing,” Covington says.

Shields has observed this too, and says the way women disclose and explore is different when there is a man in the room. Even if it’s someone they trust who is not threatening, the way women engage is different if a man is present. For this reason, Rise will be a single-sex environment; counsellors and holistic staff will all be women, as will the fitness trainers and housekeeping staff.

While there is a stigma attached to addiction, it is accepted that women have drug and alcohol issues and that treatment is a smart way to address it. The greater stigma is around issues related to trauma, such as sexual abuse or domestic violence. Women are more likely to come to a rehab centre for an addiction and only later will other issues surface. Shields says this is because women often blame themselves for any abuse.

“Women often think, ‘How come I couldn’t speak up? How come I couldn’t fight? How come I couldn’t tell somebody?’ Often clients will tell me, ‘I didn’t know how to say no’. They haven’t been educated about what is actually happening physiologically when there is trauma,” says Shields.

Education is a key component of an addiction programme and the body’s trauma response is a critical lesson. In a situation of heightened fear, the body goes into fight (the heart races and the body prepares to do battle); flight, when you get ready to run; or freeze, which often happens if fighting or fleeing are not an option.

“Freezing means shutting down so you don’t feel the pain, you don’t see the things happening, you are separate from it, you are disassociated from it,” says Shields.

The freeze response is common in cases of sexual abuse, physical violence or emotional abuse. It is a natural survival mechanism and understanding this is lesson one in a trauma-informed programme.

“You may not have identified it as trauma, but it’s every single time you’ve had to suck it up, hold it in, blame yourself, say it was you, take another drink, go into another abusive relationship, try and figure it out through a disorder eating pattern, which is it’s not OK,” says Shields.

Since The Cabin opened in 2010, 25 per cent of its more than 3,000 clients have been women. Of those 760 women, 135 have come from Asia, including 41 from Hong Kong. Of the women, 60 per cent are housewives and the rest are working professionals.

“We do see women who are no longer working in their professions any more. They are in Hong Kong with their husband and a young child and living in an expat community, and they don’t have to do anything except take the child to school. They’ve given up a lot of their identity and what was important to them,” says Shields.

The most common substance addictions among the Hong Kong women The Cabin sees are alcohol and opiates (prescription medication). The medications are often prescribed for personality disorders, such as bipolar disorder, but Shields says the symptoms are close to trauma symptoms.

“That’s not to say the diagnoses are incorrect, but that there is trauma in there as well, and they are prescribed quite substantial medications, mood stabilisers and benzos [benzodiazepines, tranquillisers such as Valium and Xanax],” says Shields.

In addition to daily group discussions, one-on-one counselling, gym sessions, art therapy and community validation meetings, the Rise programme also includes TRE – Tension or Trauma Release Exercise. This is a body exercise devised by Dr David Berceli to help an individual release the physical tension created at the time of a traumatic or stressful event.

“The body [registers] traumatic events, whether it’s the result of a natural disaster or war or the result of being neglected, bullied or psychological or physical abuse,” says Letizia Spoto, who practices TRE at The Cabin, Chiang Mai.

According to the TRE system, the body’s natural way of discharging the tension that results from trauma is to shake, releasing the excess of adrenaline and cortisol. But we tend to resist doing this because we’ve been socialised to see shaking as a sign of weakness, says Spoto. The long-term effect of not releasing that tension can mean you get easily startled or overreact to small things, she says. This is because the nervous system is in survival mode.

“TRE is being recognised as a breakthrough in stress management and trauma recovery. They [Dr Berceli] noticed that you can’t treat someone’s behaviour if you don’t treat the root of the issue, which means the body [is] not perceiving threat,” says Spoto.

Spoto introduced me to TRE. Having taken me through six simple exercises, she asks me to lie on my back on a yoga mat on the floor, feet together and knees apart. I had no idea what to expect, so the shaking took me by surprise. First my hips, then my legs started shaking uncontrollably. After 15 minutes of shaking, I stretched out my legs and the shaking stopped.

“The tremors are going through the muscles to release a lot of energy. Generally, after TRE, clients feel tired and that night they sleep like babies; it’s their nervous system calming down, not being alert or on guard,” says Spoto.

I’ve no idea what I released, but it felt good to have a good shake and I can confirm I slept well that night.

Addictions and trauma are not all the same, and programmes such as Rise recognise that.

“We are not trying to trigger people into flooding or opening up trauma, we are gently having conversations that are contextual and when we do that there is healing,” says Shields.

The last word goes to Covington, who was a pioneer in recognising the overlap between women, trauma and addiction.

“What’s important for people to understand is there is a great deal of shame people carry around because of the stigma of addiction. Almost everyone knows someone who has a problem – it’s important to know there is always hope, women can recover regardless,” she says.

Original Link: SCMP