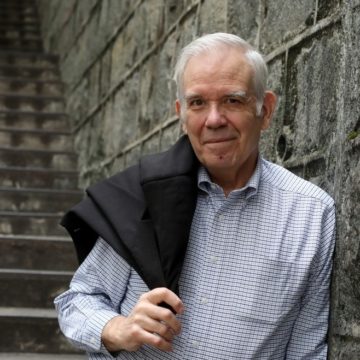

The American scholar and conservationist recalls how a picture of a footprint in a newspaper sparked a lifelong ambition to solve a centuries-old mystery

Rumble in the jungle My grandparents were cowboys in Kansas. They paid their way through medical school and after they graduated went to India to work as medical missionaries, just before the first world war. My father and his siblings were born in India. When my father was four months old, he was almost taken from a tent by a she-wolf in the jungle in north India. His nanny slammed her pith helmet against the wolf, and she dropped him.

My father, Carl Taylor, went to the United States for medical school. He met and married my mother, Mary, and I was born in 1945, in Pennsylvania. My parents travelled to India to do medical work in early 1947, just before independence, and I went with them.

My father was among the first Americans to go into Nepal in 1949 (Nepal has been isolated for most of its history and only started opening up to foreign visitors in the mid-1940s). It was a good childhood. My playmates were the village children – I spoke to them in Hindi. Today, I also speak Urdu, Nepali and some Punjabi.

Wrong footed When I was 11, I noticed a picture on the cover of The Statesman newspaper of a footprint in the snow. That was the beginning of my fascination with the yeti. The story quoted a curator at the British Museum saying the print wasn’t humanoid as everyone thought, he said it was the print of the langur monkey. I thought that was ridiculous; I played in the jungle and knew the langur well.

My father was doing community-based medicine in Nepal and we moved around a lot with him. I always asked people about the yeti. It was evident to me that we weren’t talking about a myth – it was a real animal because there were real footprints. My father went back to the US to go to Harvard University to teach the community-based approach to medicine that he had developed in India. We were going back and forth between India and the US. By the time I was 18, I’d spent 12 years in India and six in the US.

Abominable snowmen Thanks to my special childhood, I had been able to explore the Himalayas from one end to the other; even Edmund Hillary couldn’t do that because he needed an expedition and I could get on a bus and walk and eat local food and didn’t need porters. If you look at the whole range of the Himalayas, the specific portrait of the yeti is only in the Everest area. There is a different one in Tibet, a different one in Indian Himalaya, a different one in the Bhutanese Himalaya.

In 1962, we were invited by the Bhutanese king, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, to stay at the palace. The king was also interested in the yeti, so I got his interpretation of it. It was clear the Bhutanese yeti was different from the Sherpa yeti. The Bhutanese yeti is much more dangerous, it was said to take your face off. His Majesty told me, “We all call it a yeti, but actually it’s a bear.”

Now the Bhutanese are much more Buddhist-centric. Cultures evolve, just as the Dalai Lama has changed his philosophy. I worked for the Dalai Lama in the late 1960s, between my master’s degree and doctorate. I was his educational adviser when he was changing Tibetan Buddhist thinking from being animistic and tantric to being inclusive and gentle.

The Yeti trail I did my doctoral work at Harvard and it was during that time that I met the crown prince of Nepal, Birendra Bir Bikram Shah, who was a student there (Birendra was the king of Nepal from 1972 to 2001). The Vietnam war was going on and I had no intention of murdering people or dropping napalm on them, so the US State Department grabbed me and I went out to Nepal in a remarkably senior position for a junior individual, partly because of my linguistic and cultural abilities.

I spent three years there, from 1968 to 1971; in my position in charge of family planning, I had access to a helicopter, which also allowed me to do yeti research. Every time the chopper landed, I’d ask people about the yeti. Big yeti expeditions had been organised by newspapers such as the Daily Mail in the UK (in 1954) and the millionaire Tom Slick. They would all come with the expedition model while I was just out there doing research.

Bear facts In 1983, I was able to identify that the yeti was an Asiatic black bear. This was a theory that had been advanced many times since the 1930s, but I was able to prove it by tranquillising my friend the king’s bear in a Kathmandu zoo. My contribution was being able to replicate in plaster of Paris all the mysterious footprints that other people had not been able to explain. By repositioning the feet of the bear in plaster of Paris, I was able to show that the Eric Shipton print and the Tombazi print were made by a bear.

If you have a house cat, you will notice that as it walks it always puts its hind foot in front of its front foot – all cats do that because it makes less sound. But if the cat is going uphill, the hind foot falls back a bit. So, what was a round print becomes longer, foot-like.

Out of the parks When I solved the mystery of the yeti, I realised that the really interesting question was how we preserve its habitat. It was clear to me that the human species was destroying the planet. The basic model used for national parks was based on Yellowstone National Park, in the US, which relies on policing the park, putting in a warden, defining a perimeter. It was a flawed model – not only was it expensive, you create these little pockets of wilderness. The issue was not really the park, but what was happening outside the park, so I made a career shift to focus on the stewardship of the planet, nature conservation.

Border crossing We created Makalu Barun National Park (established in Nepal in 1992), which was the first community-based national park, an extension of Sagarmatha National Park. I realised there was a fabulous area just north of the border. My father was the Unicef ambassador in Beijing. He had got to know influential people in China, so he said to Lin Jiamei, the wife of president Li Xiannian, “My son would like to go into Tibet.” Although Tibet was closed, they arranged a permit.

So, I went into Tibet to propose a national park. I had this idea that it should also be community-based. We had been working in the Tibet autonomous region since 1985 under the support of vice-chairman Mao Rubai. After Hu Jintao came to the region in 1988 (as party secretary), the Qomolangma (Mount Everest) National Nature Preserve was formally gazetted, in 1989. Together we developed a system of national parks for China and today there are 18 nature preserves and national parks in Tibet; 54 per cent of Tibet is now protected under conservation management and it was zero when we started. This all began with the yeti.

Call of the wild We have more sightings of yetis today than we did 50 years ago. As we create this new age where humans dominate the planet, we are having to also create our own folklore and legends about what the planet used to be. As we have changed the human species, we have the psycho-emotional need to connect to where we came from. That’s why we have more yetis.

The yeti is the embodiment of people and nature in the same persona. Behind the intriguing mystery of the footprint, which I thoroughly enjoyed, there is the much more important point that, if we are going to have a human future, we’ve got to have a human relationship with the planet – we can’t separate ourselves from the wild.

Original Link: SCMP