Artists painting a picture of protests for the world

— July 18, 2019

- A group of artists are using art to immortalise the summer of unrest that is gripping the city because of the controversial extradition bill

July 1, 2019. Causeway Bay. It’s 32 degrees Celsius [90 degrees Fahrenheit] but feels even hotter on the crowded street. The black clad protesters carrying placards, umbrellas and mini electric fans shuffle along Lockhart Road, one of the main arteries in the busy shopping and entertainment area of Hong Kong Island.

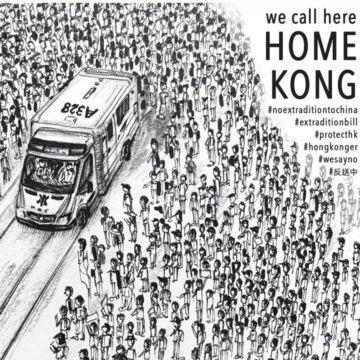

On the side of the road, a woman in her 20s hands out postcards featuring black-and-white sketches she’s been producing since the start of the protests against a now stalled extradition bill. The controversial bill would have allowed the transfer of fugitives to China and other jurisdictions which the city does not have a deal with.

Kay Wong, who has been drawing since she could hold a pencil, turned to social media to express her fears at what is happening in Hong Kong, posting her first sketch in response to the bill on June 12.

When a Facebook follower asked if she could print the sketch as a postcard to send to friends overseas, Kay Wong had an idea. She decided to use her work to help inform the rest of the world about the plight of the protesters in the semi-autonomous city.

“After two million Hongkongers protested and yet the government still kept a tough attitude, we felt hopeless. What can we do next? Maybe we can attract the attention of the world. We want people who can stand with us, stand with Hong Kong,” she says, referring to the march which drew an estimated 2 million people on June 16, according to organisers.

Kay Wong doesn’t know how many of her postcards have been printed, because she made the soft copy freely available online for people to download and print, but she says she’s received very positive feedback.

“As an artist, I strongly believe that the extradition bill will strangle the freedom to create. There are so many dissident artists in China who have asked for asylum in other countries. They can’t create things with a political element … Creativity should not be retrained,” Kay Wong says.As with the 2014 Occupy protests, also known as the “umbrella movement”, art and visual works are playing a key role in the extradition bill protests – which, since the city’s leader said was “dead”, have also morphed into calls for greater democracy. The works are creating bold visuals that capture the key issues.

But this time around things are different, and the changes reflect the way the protests have evolved.“There are almost no professional artists creating works and using their name. It’s a reflection of the movement itself – leaderless and anonymous. We saw what happened in Occupy. People have learned to be careful about using their names,” says academic, artist and independent curator Sampson Wong Yu-hin.

He points to a series of graffiti images portraying police brutality. “The graffiti is done by a team of very young people. Only one is an artist, the others are students,” he says, adding that some of the most humorous and playful responses to the bill have come from the general public.

Take “Say No to China Extradition”, a one-and-a-half-minute video that uses slick black-and-white animation to make clear the protesters five demands. Sampson Wong Yu-hin describes it as the most distinctive artwork to come out of the movement.

“The team did not disclose who they are, but clearly they are professional. A lot of people who are very well educated and have a very good understanding of the social movement are participating in driving the movement, but not disclosing who they are,” he says.

Subtitles for the video have been translated into 20 languages, including French, Polish, Korean, Vietnamese, German and Dutch. He says artists and activists are working smart and actively looking for networks to get a wider, global reach.

“I think it’s a conscious decision – some of the artworks and designs are consciously designed to talk to the world,” says Sampson Wong Yu-hin, who was active in the “umbrella movement”. A photograph of him holding a banner reading “The People’s Will is Here” was widely shared in the media.

He is currently working with a team of volunteers to archive the images that are being produced during the protests, in particular the “Lennon Walls”, which sprang up across the city last week, plastered with protesters’ Post-it notes.

The delicate nature of much of the work – usually written in black pen on paper – and the enthusiasm with which pro-Beijing supporters are taking down such works means they have to act fast.

“We are photographing all kinds of graffiti and posters and images. I’m going to launch a website to show these images. And I’ll set up an Instagram site … as an immediate solution until the website is up and running,” he says.

The Hong Kong Artists Union has been at the forefront of collective action. It joined the June 9 demonstration – which organisers said drew an estimated 1 million people to the streets – and made props and banners to distribute during the protest.

On June 12, the day that the controversial legislation was expected to be discussed in the legislature, the union wrote an open letter calling for an industry strike. More than 100 arts organisations, including many big galleries, joined in the strike, shutting their doors and freeing up their staff to join the demonstrations. And it has continued to participate, holding sketching workshops around the government headquarters.

“Our artist members are concerned about freedom of speech in Hong Kong. After the violent acts by police and people seen bleeding on the streets, we care about the next generation. We want a brighter future,” says Wong Ka-ying, a convenor of the union.The city’s police force has come under fire for their handling of protesters – in one instance, several protesters were shot in the head with rubber bullets – but the police chief has rejected accusations of excessive use of force, saying that his officers were also in grave danger. The latest clash in Sha Tin, on Sunday, left 22 people in hospital. At least 10 of those injured were police, including one who lost part of a finger.

The artists’ union was established in 2016 and has seen its membership grow from 300 members to 400 over the past month or so. Its members range from students to well-established and senior artists.

Wong Ka-ying is one of the few union organisers who is willing to identify herself. She says that though a lot of artists want to get involved and support the cause, many are fearful of possible repercussions and prefer to remain anonymous. She says many artists self-censor because they are fearful of the government.

“I face questions from curators, institutions and collectors, such as, ‘Do you have work that is less political because this is a sensitive time, politics makes it difficult’. It’s soft pressure to the artists. ‘If you are worried about your future career you should stop doing things with politics’ – we get that a lot,” the 28-year-old says.

Visual artist Kacey Wong Kwok-choi is a member of the union and has been involved in its activities as well as staging his own response to the extradition bill. On July 1, dressed all in black and wearing a mask, he waved a large black version of Hong Kong’s red-and-white bauhinia flag on Harcourt Road in Admiralty.

“It was a performance-based work. Live art. The black flag represents ‘live free or die’. That’s the spirit of the time right now. The young people want to live in a free society, and they are willing to sacrifice their lives for it,” Kacey Wong Kwok-choi says.

He was particularly struck by a piece of graffiti on a pillar of the Legislative Council that translated as “It was you that told me that peaceful demonstration is useless”, and is not surprised that the peaceful demonstrations have spilled over and led to more skirmishes between protesters and police.

As the artists’ union continue to grow, Wong Ka-ying says she is proud of the fact that artists have come together to support each other.

“Artists think that they are little, and their voice is not important, but when we stand as one then our voice matters. Together we can do more, we are not competitors but companions,” she says.