Life and career of the reigning queen of pop

— April 23, 2015Reigning queen of pop Katy Perry is bringing her lavish stage show to Macau

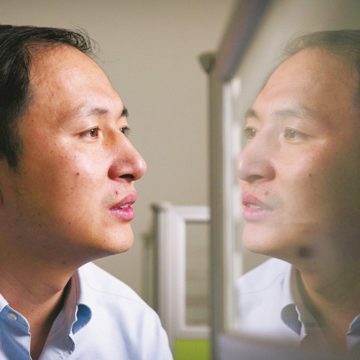

When Chinese scientist He Jiankui walked onto the stage at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in November last year to defend his creation of the world’s first gene-edited babies, he was already the focus of global attention and facing a barrage of criticism from his peers.

The scientist had in previous days announced the birth of twin girls – the world’s first gene-edited babies – unleashing a storm of criticism from scientists around the world.

Now, months later, questions continue to be raised about the consequences of the precedent-setting experiment.

It was day two of the summit, hosted in Hong Kong by the University of Hong Kong (HKU), and many doubted whether He would actually appear.

The day before, one of China’s leading bioethicists, Professor Qiu Renzong of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, had slammed He’s gene-editing announcement, saying his experiments did not have “the least degree of ethical responsibility and acceptability”.

Dr Derrick Au Kit-sing, director of the Centre for Bioethics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, was sitting in the third row of the packed HKU auditorium to hear He’s defence of his controversial experiment.

Like many others, he sat dumbfounded through He’s 20-minute presentation, snapping iPhone photos of the slides.

“These things don’t happen ad hoc or spontaneously,” said Au about Qiu’s reaction, at a recent presentation at Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club.

“If Professor Qiu decided to hit hard on day one, I think the line had already been taken [in mainland China] on the government’s position on the subject.”

Au, who works to try to improve public understanding of bioethical issues, suggested that He had no official support from the Chinese government for his actions.

He, who has since been dubbed “China’s Frankenstein”, had used CRISPR technology to edit the baby girls’ DNA while in embryo – a procedure that scientists warn could have unpredictable and far-reaching consequences on their future health and longevity.

Nearly every cell in their bodies now carries the altered DNA, which He had edited to make them more resistant to HIV (their father was HIV-positive), and these “germ line” inheritable changes would be passed on to their children.

CRISPR gene-editing can go wrong, too, potentially leading to “off-target” changes elsewhere in the genome that could even lead to cancer.

Nicknamed Nana and Lulu, the baby girls are the living consequence of a rogue experiment by a scientist who decided to break the rules.

For his part, at the summit He apologised for the outrage he had provoked but defended his controversial experiment and said he was proud of the results.

He also said he had followed guidelines of embryo editing laid down by the US National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine in 2017. These guidelines, which many believe were not stringent enough, are now being more carefully rewritten.

Many nations around the world, including the US (where He trained) and China, ban the deliberate alteration of genes in human embryos, although loopholes can be overlooked.

Then working at the Southern University of Science and Technology, in the Chinese economic powerhouse of Shenzhen – he was fired in January this year – He faced an onslaught of questions from the media and his peers at the summit, most of whom have raised doubts about his claims or condemned his brashness.

Two weeks before the now notorious November summit, Au had met the controversial scientist at the National Bioethics Conference in Shanghai.

Au got the sense he was an intelligent, composed, credible and tech-savvy individual. He had even suggested he give a talk at Chinese University in the future, and watched him engage in a lively debate.

“There was a special parallel session about ‘Will the chaos of gene editing take place like scandals of stem cell therapy in mainland China 10 years ago?’” Au said, referring to what was then a growing trade in unproven treatments in China, attracting desperate patients from around the world and potentially damaging the reputation of stem-cell research.

“So, this is one clue that this isn’t something that happened in isolation – people on the mainland knew some problem may arise in this field.”

And there certainly was a problem – more than 120 Chinese researchers signed an open letter criticising He for his “crazy and unethical” work with the gene-edited babies.

And in January, a preliminary investigation in southern China’s Guangdong province found He had defied government bans and conducted the research in the pursuit of personal fame and gain.

It claimed he had created a fake ethical review and recruited eight volunteer couples (the males tested positive for the HIV antibody, females tested negative) and carried out experiments from March 2017 to November 2018.

As HIV carriers are not allowed to have assisted reproduction in China, He swapped the blood samples with those of healthy individuals so that the hospital would not know they were working with an HIV carrier.

The details remain murky to this day. “We don’t know if this is the full picture,” Au said.

A couple of weeks later, four prominent bioethicists, including Qiu – “the grandfather of bioethics in China”, according to Au – and Xiaomei Zhai, president of the Chinese Society for Bioethics, published an essay condemning the Guangdong investigation as inadequate.

They argued that the informed consent He obtained was invalid and that the investigation did not say why or which crimes he’d apparently committed.

They also noted that He had been given the opportunity to appear on a programme on China’s CCTV state broadcaster to promote his so-called third generation of DNA sequencing device.

“Who gave him such a very rare opportunity? Might he have had the support of an interest group with power at the departments of local or central governments?

“If so, the group should be accountable for its involvement in promoting He’s illegal research,” the bioethicists wrote.

Even if it was a simple criminal matter, they argued, why wasn’t everyone who helped fund the hugely expensive research exposed?

“That was meant to tell the world that the government and ethicists in mainland China are really serious, they don’t think this is a case [that] closed with the investigation,” Au said.

But despite the scandal of the gene-edited babies, playing host to the human genome editing summit in November was a good thing for Hong Kong on a couple of fronts, he explained.

“It makes Hong Kong more credible because we are able to openly discuss those issues from day one. It’s also a good thing for public engagement – it’s not often you get such intense attention on a subject matter like that for so long,” Au said.

Hong Kong’s conservative research culture criticised

One of Hong Kong’s biggest stars in medically related genomic research is Professor Dennis Lo Yuk-ming at Chinese University.

Lo invented a technique to use fragments of fetal DNA in a pregnant woman’s blood to piece together the genomic information of the baby for diagnosis. The technology has been used to create a test for Down syndrome screening.

“We have pockets of excellence – things that we can name where we are ahead of the world in medicine,” Au said. “For instance, Queen Mary [Hospital] can do really good spinal surgery that is ahead of Asia.”

But he says Hong Kong’s general research culture is conservative and lags behind the rest of the world in terms of innovative technology.

“Technological solutions are not yet mature enough. People don’t venture into it enough because there is still a separation between the academic community and venture capital and technology enterprise,” he said.

Ten years ago, Singaporeans were coming to Hong Kong to learn from the city about health-care issues, but Au said the Lion City’s thirst for talent means it has now outpaced Hong Kong.

“They [Singapore] actively use their big radar screen to identify people that they can headhunt and invite to Singapore to jump-start certain fields. Now we are finding ourselves playing catch-up and we have quite a long way to catch up.”

Even Taiwan, which has a long history of openly learning, particularly from the US, is ahead of Hong Kong, Au said.

“They [Taiwan] are more in sync with the rest of the world. We are becoming more inward looking.

“It’s unfortunate with the recent turn of events in Hong Kong – the government was really onto trying to jump-start more collaboration and open projects in technology and innovation, but now it’s interrupted so we are not sure.”

Original Link: SCMP