Making of an iron lady

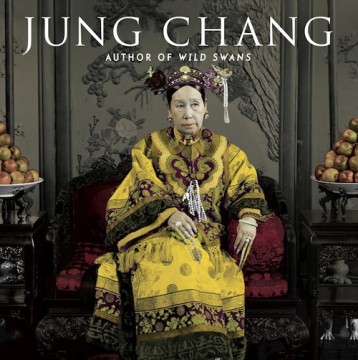

— October 6, 2013Jung Chang’s biography casts a forgiving light on the life and reign of the woman who dominated China’s history during a period of upheaval

Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China

by Jung Chang

Jonathan Cape

4 stars

The Empress Dowager Cixi has been called many things – cruel, ruthless, treacherous, even sex-crazed. She has been blamed for a host of atrocities, as well as for the fall of the Qing dynasty.

Jung Chang is out to set the record straight.

In the eight years since the publication of Mao: The Unknown Story – the biography she wrote with her husband, Jon Halliday – Chang has been researching the life and times of the most significant woman in China’s history: for almost half a century, Cixi ruled over one third of the world’s population.

Chang’s publisher tells us that it’s in light of newly available historical documents – court records, diaries, official and private correspondence, most of it in Chinese – that she was able to produce this comprehensive and sensitive biography, but there’s no doubt it’s also in large part thanks to a biographer who was willing and often even eager to re-examine Cixi in a less critical light.

Cixi is far from being the first female ruler to come in for bad press, but the slanderous vitriol against her was especially harsh – and the name-calling continued for almost 100 years. Only in recent years have historians been prepared to view events in a more sympathetic light. While Chang isn’t the first biographer to trumpet Cixi’s achievements, her book will certainly make the greatest impact.

Chang paints the empress dowager as a complex character: stern-faced in politics and yet giggly, even girlish, among her court ladies and eunuchs; forward thinking and eager to embrace the modern world yet superstitious; capable of impulsive acts of cruelty and also ones of great kindness. Expertly, Chang builds up the layers of detail until we have that lofty sense of seeing the world through Cixi’s eyes. We feel her drive and ambition, sense her fear and want her to succeed.

Readers who found Chang’s Mao Zedong biography slow going, a little too dry and heavy on the historical detail need not worry about that here. Vast sections of Empress Dowager Cixi are as engaging as good fiction – the characters are carefully drawn, the plot compelling. It’s page-turner stuff.

Chang is a confident narrator and here she’s doing what she does best: recounting China’s history through the eyes of a woman. She did it to great acclaim in 1991 with her debut work, Wild Swans. By telling the story through the eyes of her grandmother, mother and herself, she was able to bring the reader up close and personal with the dramatic events that shaped China, a unique perspective that she managed sensitively. And she does it again with Cixi, getting right under the empress’ skin.

Perhaps the most surprising element of Cixi’s story is that she ever became the empress. It certainly wasn’t handed to her on a plate. She came from a good Manchu family and, although she lacked a formal education, she made up for it in intuitive intelligence.

As a young girl, barely 11, her family fell on hard times. The eldest of two daughters and three sons, she offered ideas to her father on what the family should do to get out of debt. The suggestions proved sound and her father treated her like a son, discussing money matters and business, which was unusual for a girl at the time and helped shape the person she was to become. It’s such details that give Chang’s portrait a convincing depth.

Cixi’s story begins in 1852 when as a 16-year-old she was chosen from hundreds of young Manchu girls to join Emperor Xianfeng’s harem. The emperor was only 21 and nicknamed “the Limping Dragon” owing to his poor health, but he had a healthy appetite for sex and in addition to his 19 concubines at the Forbidden Palace, he had prostitutes brought to him when he stayed at the Summer Palace. Cixi was a low-ranked concubine and not especially popular with the emperor, managing to rub him up the wrong way by daring to advise him on state affairs. She did, however, cultivate a good friendship with the empress, a concubine who had joined the harem at the same time as her and who had risen quickly through the ranks. Cixi’s luck turned when she gave birth to a son, the emperor’s first-born male child. This elevated her to the No 2 consort seat, after the empress.

And so began the roller-coaster ride of Cixi’s life in the Forbidden City. When her son was five years old, the emperor died and Cixi, barely 26, rose to the occasion. It was to be the first of many bold and savvy moves. Colluding with the empress and playing a little on the assumed naivety of a concubine, she staged a coup against the regents appointed by her husband and made herself the ruler of China.

Officially her son, Tongzhi, was in charge, but given his youth Cixi called the shots and she did it all from behind a yellow silk screen, part of the court protocol that dictated she couldn’t see men or be seen by them, even her court officials. She felt claustrophobic in the Forbidden City and longed to travel, but respected the strict decorum demanded of her.

This delicate balance was maintained even while she pushed for China to enter the modern age. She sent envoys around the world to see how other nations were doing things and when they came back she savoured their tales and determined that China would adopt the best the modern world had to offer.

Cixi was a champion of electricity, the telegraph, the railway, industries, and an army and navy with up-to-date weaponry. She saw international trade as the key to her efforts to “Make China Strong” as well as expanding education, even sending teenagers overseas to broaden their minds. And it was Cixi who brought an end to archaic practices such as foot-binding and gruesome punishments such as “death by a thousand cuts”.

But these breakthroughs came towards the end of her life. Before then there was much bloodshed and we are privy to some of Cixi’s more rash, draconian decisions – in a hurry to leave the Forbidden City, she has her adopted son’s favourite concubine thrown down a well.

What draws the reader to her is not that she’s nice or especially kind, but that she’s human. In her 20s, her husband dead and barred from seeing men, Cixi falls for one of her eunuchs, Little An. It was hardly surprising, the eunuchs were the only men – if somewhat lacking – allowed in the harem. And when one of her rivals in the court finds an excuse to have Little An executed and Cixi collapses in despair, the reader is tugged into her story. It’s one of many dramatic points in a life less ordinary.

Equally delicious amid the high court drama are the little details of life within the Forbidden City. We learn how the eunuchs were chosen and the complications often associated with castration, we see Cixi’s weakness for Pekinese “sleeve” dogs and discover how she delighted in having her photograph taken (especially when her face was retouched to look 40 years younger).

Chang isn’t out to portray her as a saint, but as an exceptional woman and leader. Right up until the very end of her life Cixi was making tough decisions. Gravely ill and concerned that if she died the country would fall into the hands of the Japanese under her adopted son’s rule, she arranged to have him poisoned, then hurriedly named her great-nephew as his successor. She was working – settling court matters, arranging wills – right up until she died the following day.

Twenty years after her death when the Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek established a new regime, an unruly army unit used dynamite to blast into Cixi’s tomb. They ransacked it, stealing the jewels and tearing off her clothes and pulling out her teeth in search of possible treasure. Her corpse was left exposed and Chang explains that as a firm believer in the sanctity of the final resting place, this would have upset her.

This careful work – heavy on detail and full of drama – has waited a long time to be told and you’ll reach the end with a sense of having known this formidable woman.

Original Link: SCMP

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/118-SCMP-Jung-Chang-1.pdf]

[PDF url=https://www.hongkongkate.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/118-SCMP-Jung-Chang-2.pdf]