‘No one asks to become addicted’

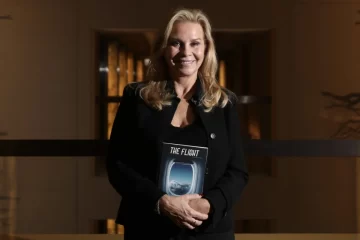

— November 26, 2023Cammie Wolf Rice shares her struggle to make sense of losing her son to opioids in her new book, and how she helps parents take steps to prevent similar deaths

Cammie Wolf Rice is a woman with a fire in her belly. Every opportunity she has to speak her truth, she does not hesitate to take the microphone. She knocks on doors, determined to strive for change. If she did not, the pain of loss would overwhelm her.

“There is no worse pain than losing your child. I had a choice – I could either stay in the fetal position or take that pain and turn it into purpose,” says Wolf Rice, who lived in Hong Kong for seven years from 2011 and was back this month to speak at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Central, Hong Kong Island, about her new book, The Flight: My Opioid Journey.Her son Christopher was diagnosed in junior high school in the United States with ulcerative colitis. When he was a senior in high school in the early 2000s, he had surgery to remove part of his colon.

He was sent home with 90 OxyContin pills, the new wonder drug. It was a big operation and her son was in a lot of pain, so Wolf Rice did not doubt the doctor’s orders.

“I gave them to him every four hours as prescribed. I didn’t think to question if it was OK or safe,” she said.

But it was not safe. Twenty years ago, no one had heard of the risks of opioid addiction. Christopher was given another prescription and then another; it led to an addiction that he fought for the next 15 years.

In 2016, Christopher died of a heroin overdose on a family holiday in Cambodia. The stigma around addiction is so great that it was two years before Wolf Rice could tell people that her son overdosed.

“If you say your kid has cancer you have people coming to your door and giving you casserole dishes. But with addiction you hide it under the rug because you don’t want to be looked at as a failure as a parent. What’s wrong with my son?

“I wanted Christopher to have a respectable death, I didn’t want the whispering going on,” she said.

She decided to tackle the problem head on, looking at how to stop addiction before it even starts. Many times, that is with a hospital visit.

“Eighty per cent of heroin users started with a painkiller that came from a doctor, so we have to look at being health advocates for ourselves. People don’t wake up and say, ‘I want to be an addict today’. No one asks to become addicted to opioids but literally it can happen with one prescription,” she said.

She helped launch a clinical trial in her home city of Atlanta, in the US state of Georgia, at Grady Memorial Hospital to test out the viability of having “life care specialists” in hospitals.

This would be a new position, someone to sit down with a patient and explain that the medication they will go home with is an opioid, that it is an addictive painkiller, and they will need to taper off quickly.

These life care specialists also shared pain management techniques that are non-addictive.

“Seventy per cent of the patients we saw didn’t know they were taking an opioid or didn’t know what an opioid was. You’ve got a problem right there,” she said.

That pilot programme was a success and is now being rolled out in nine rural hospitals in the US. She also recently got a US$200,000 grant from the NFL [National Football League] to have life care specialists to support American football players, advising them on pain management before and after surgery.

Her long-term goal is to get these specialists into every hospital in the US. Is she considering Hong Kong?

“I really am connected to Hong Kong, I would love to see life care specialists in Hong Kong. It’s about the funding. I have all the curriculum for the life care specialists online, so it’s doable,” she said.

The years that Wolf Rice lived in Hong Kong, she spent a lot of time flying back and forth to the US where Christopher was in treatment for addiction, making sure she was there to see him at the family sessions.

She chose the title of her book – The Flight – because she had spent so much time on planes and also because she sees it as a fitting analogy for life.

“We land at different places in our life – happiness, sadness, grief, illness – and we have to keep flying and refuel and keep going. You never know who is going to leave your flight unexpectedly and you don’t know who is getting on your flight,” she said.

In the middle of writing the book, in 2021, another tragedy struck. Her brother, who had been having a hard time during the Covid pandemic and experiencing high anxiety, was given a Xanax tablet by a friend who was visiting. The Xanax was poisoned with fentanyl, and he died.

“For me to lose my son in the opioid crisis and then my only sibling to the fentanyl crisis, from a spiritual standpoint, I thought, ‘OK, I have been chosen’. This is the only way to survive, I’m a voice. I have a fire inside of me,” she said.In early November, Hong Kong customs officers seized their largest haul yet of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 100 times stronger than morphine. The 3kg (6.6 pounds) of the drug was concealed in a shipment of air compressors.

“Fentanyl is coming from China, going to Mexico where the Mexican cartel has pill mills and they are mass producing. They are not chemists doing this, they are the cartel,” says Wolf Rice.

When fentanyl takes someone’s life, it is not an overdose because it is medicine that is being poisoned with fentanyl. Drug dealers create fake pills, such as Xanax and Adderall, and lace them with trace amounts of fentanyl to get their customers addicted.

“If they get you addicted to fentanyl, you are a great client, coming back multiple times in that day, so they don’t care who they kill on the other side,” says Wolf Rice.

Mark Willett, an addiction counsellor working mostly with expatriates in Hong Kong, says the opioid and fentanyl crisis has not reached the city.

“The majority of clients I see are mostly struggling with alcohol, cocaine and meth. Those struggling with opioids and heroin are in a minority,” says Willett.Ronnie Pao, a psychiatrist specialising in addiction, echoes that. “ Fentanyl is a big problem in the US, but we rarely see issues with it in Hong Kong. But we need to be aware of it and keep an eye on it. I’m sure there are users, it’s about proportion,” he said.

Wolf Rice says the people in addiction know about the risks of fentanyl. She wants to reach the young people and parents who do not know, and encourages parents to get informed and have frank and open conversations with their children, especially those who are preparing to go to college overseas.

Better still, have a trusted family member or friend have that conversation.

“Kids have the tendency to say, ‘Mum doesn’t know what she’s talking about’ or ‘Dad’s just being a nervous Nelly’. An uncle, neighbour or godmother can have that conversation with your child.

“Have them say, ‘People have experimented for years and years. This is a different playing field – it’s poison. You need to be aware they are in every street drug. Do not take anything from anyone – they are poisoned,” she says.

Partnership to End Addiction (drugfree.org) has excellent resources to support parents, and guidelines on how to have those conversations.

“Fentanyl is not overdose. You took one pill, it is laced with poison, you are dead. That’s not an overdose, that’s a poisoning. It is murder,” she says.

Original Link: SCMP