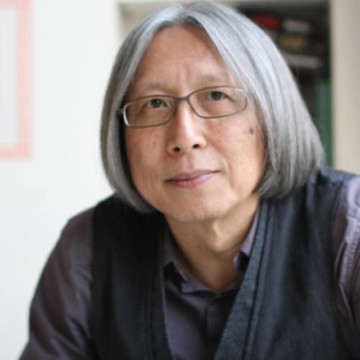

Chan Koonchung remains banned, but big in China

— May 21, 2014Chinese novelist Chan Koonchung says he writes for “his Beijing friends” though they can’t buy his books. Here, he discusses censorship, Tibet and his new work.

The Unberaable Dreamworld of Champa the DriverThe Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa The Driver is a fast-paced read, packed with sex and danger. An exploration of the relationship between China and Tibet, it has the makings of a cult novel. The Chinese version was published in Taiwan and Hong Kong last year and the English translation – by Nicky Harman – is out now.

“In 2008 I could see China going through a new stage, it was the beginning of a new normal, but my Beijing friends didn’t believe me, so I wrote The Fat Years to try to convince them. It’s always my Beijing friends that I write for,” says Chan.

Smuggling Copies Into China

Chan smuggled copies of The Fat Years into China in his suitcase until it made its way online and went viral. The Chinese Government has since largely deleted it, but occasionally it crops up.

Chan smuggled copies of The Fat Years into China in his suitcase until it made its way online and went viral. The Chinese Government has since largely deleted it, but occasionally it crops up.

“I still sometimes find comments on Weibo from someone who has just discovered it. I think books will find their way to get to the people, whoever wants to read it,” says Chan.

For a Chinese writer, not being published in China is to miss out on a massive market, but Chan’s says it’s a sacrifice he’s happy to make if it allows him the freedom to write without self-censorship. Besides, he’s doing well outside China. The Fat Years was translated into 14 languages and the French and Dutch translations of The Unbearable Dreamworld of Champa The Driver have already been snapped up.

Born in Shanghai, Chan was raised in Hong Kong and left in 1992 to live in Beijing, then Taiwan and is back in Beijing again. For a banned novelist Beijing is potentially a risky place to live, but he says he couldn’t write unless he was on the ground and in touch with life in the capital. That’s not to say he isn’t a little nervous.

“Anything can happen to you there — it’s up to the government. Somehow they haven’t come for me yet – I don’t know why,” he says.

Writing About Tibet and China

The Fat YearsChan has wanted to write about Tibet and its relationship with China for 20 years. It was in the late 1980s that he first visited Tibet while researching a film for Francis Ford Coppola about the 13th Dalai Lama and his relationship with Englishman Charles Bell. The movie never got off the ground, but his interest in Tibet was piqued and he soon got a Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Khyentse Norbu, known internationally for directing the film The Cup about two football obsessed Tibetan monks.

“I would consider myself a not too disciplined Buddhist. I’m more loyal to my teacher than to Buddhism,” says Chan.

The Fat Years, a dystopian novel, covered a lot of ground, but Chan says he consciously stayed clear of ethnic issues because it was too big a topic.

“Right after The Fat Years was published I started working on a novel about ethnicity – in China they call it the “nationalities issue” – and the only ethnic group I knew about aside from the Han Chinese is the Tibetans,” says Chan.

Fiction about Tibet tends to fall into one of two categories either a romantic account of old Tibet, thick with nostalgia, mysticism and prayer flags (think James Hinton’s 1937 Lost Horizon). Or else it’s a fiercely political polemic that lashes out at the injustices meted out to Tibetans.

Defying Stereotypes

“These are the two most powerful stereotypes — the romantic stereotype and the victim stereotype – but if you live among Tibetans for a while you know it’s not the only story. They want to live a modern life, they want to have fun,” says Chan.

“These are the two most powerful stereotypes — the romantic stereotype and the victim stereotype – but if you live among Tibetans for a while you know it’s not the only story. They want to live a modern life, they want to have fun,” says Chan.

Champa, the young Tibetan driver who is the protagonist and narrator of Chan’s new novel, certainly has fun. The chauffeur to a successful Chinese art dealer, Plum, life is simple – until he starts sleeping with his boss and it gets complicated fast.

Wealthy, successful and older, Plum is the one with all the power in the relationship. It’s not unlike the relationship between Tibet and China, but that relationship is even more complicated than an affair with a powerful woman and Chan delves further into its complexities through a second love affair Champa has with Plum’s daughter, Shell.

Champa’s road trip from Lhasa to Beijing is one of the highlights of the book. Driven by lust and longing, he tracks down Shell and discovers she’s an animal rights activist, very bohemian and possibly bisexual. With such a massive cultural divide, it’s not a great match. Nor is life in Beijing as exciting or welcoming as he’d dreamed and he soon finds himself working as a security guard in a “black jail.”

Beijing’s “black jails” are small hotels in the capital that are used to illegally detain petitioners who travel from all over China to petition for justice. The government denies their existence and Chan says many Beijing residents haven’t even heard of them because they are not reported in the mainstream press.

Chan plans to begin work on another novel about China later this year. He won’t be drawn on what’s its about — as with most of his projects, he’s got a number of frameworks in mind and has no idea yet which one will come through — but one thing is certain, it won’t be a sequel to Champa’s story.

“I don’t want to press my imagination forward, it may not be too good for Champa,” says Chan.

Original Link: Publishing Perspectives