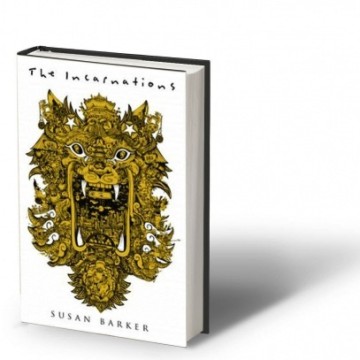

Past lives haunt Beijinger in intriguing novel

— July 6, 2014Gripping novel spans centuries in China as modern Beijinger is stalked by sinister mystery soul mate

The Incarnations works on a number of levels, pulling together so many strands of history and perspectives and drawing them into a compelling and convincing tale. Part history, part love story, with good doses of horror, comedy and philosophy, it is ultimately a thriller and a page-turner. In less capable hands, such a daring undertaking could so easily have flopped, but Barker has polished it well and the reader never so much as glimpses the cracks in the magic that is fiction writing.

The book begins with a letter written to middle-aged Beijing taxi driver Wang Jun. The writer claims to be his soul mate and to have known him for many lifetimes. But this is no love letter. As with the ones that follow, there is a chilling undertone to the correspondence: “I pity your poor wife, Driver Wang. What’s the bond of matrimony compared to the bond we have shared over a thousands years?”

Wang is rattled. Who is stalking him? What do they want? The identity of the letter writer is kept secret until the closing pages but we are treated to intimate details of the lives the writer claims to have shared with Wang.

The letters – short stories within the framework of the novel – make for compulsive reading. Each tells of a life the two have shared, dipping into the vast pot of China’s history and revealing the details of their lives against a rich historical backdrop. The stories run in chronological order from the time they are young slaves struggling through the Gobi Desert to escape the Mongol invasion, to the Ming dynasty where Wang is a concubine plotting the murder of a sadistic emperor all the way through to their lives as Red Guards during the 1966 Cultural Revolution.

It wasn’t just the circumstances of those lives that were difficult, so was their relationship: each time their coupling is dark and destructive. There is sexual violence, abuse and aggression. The power dynamic between the two alternates – one lifetime the abuser, the next the abused – and every time it ends in a violent death. The letter writer recalls killing Wang: “Blood vessels bulge in your temples, and you flush with blood as I throttle you.”

If you thought “soul mates” implied an eternally caring, loving bond, think again. Here they are locked in a destructive cycle of abuse and betrayal, and that dark pattern is mirrored in the rise and fall of emperors, conflict and war. History repeats itself, the personal and the political. We are forever condemned to keep making the same mistakes.

The research Barker has done for the book is phenomenal. She was almost 30, but already with two books under her belt, when she moved to Beijing in 2008 to work on the novel. It took her six years to write and the hard graft is visible in not only the scope of the work but the detail.

The six past lives are richly textured, with colourful descriptions of the streets, the interiors of the houses, what people are wearing, the food they eat, the smells and sounds. She paints such a convincing picture, coupled with the intense relationship between the two, that the effect is explosive.

She’s equally adept at modern China. She hasn’t just lived in Beijing – she has stewed in it, soaked up the flavour of the city, the sights, smells and sounds and recreated it on the page. Some of the best contemporary sections of the book come when Wang is driving his taxi around the city – the trail of Beijingers who pass through his cab are the real deal.

Barker may be an outsider in the sense that she’s British born and bred – her father from England, her mother Malaysian Chinese – but it’s obvious she has rubbed up close to Beijingers. She knows them and weaves them seamlessly into her overarching narrative. And she hits on some of the hot topics of the day – homosexuality, the position of women in society and more.

Don’t assume that all this impeccable historical research means it’s too lofty a tome for saucy sex scenes. Far from it. There’s a lot of sex – and little of it is the vanilla variety. In fact, some of the sex scenes reveal the best of Barker’s best research. Take the Ming dynasty lifetime where the concubine writes about “riding the unicorn horn”. Barker doesn’t skirt around it: she rolls up her shirt sleeves and gets right in there.

Nothing seems to faze her, no perversion too twisted no sexual more too sadistic. In the Tang dynasty lifetime, Wang is a eunuch (the description of his castration is horrific) and the narrator is his half-sister who works in a brothel where men indulge in sexual perversions, from urinating on women to penetrating them during their menstrual cycle and, as the madam of the house says: “Some men like to poke a women in the back passage, which is called pushing the boat upstream.” And then there’s the harem where the Emperor of Knives enjoys slashing his concubines for his sexual satisfaction.

Wang, who has a wife and six-year-old daughter, becomes increasingly anxious as the letters continue to arrive. Who is this person who claims to know him so well, following him now in 2008 Beijing and insisting on having shared intimate lives with him in the past? The narrator’s voice is absorbing and alarming, gnawing at Wang until his nerves are badly frayed: “History is knocking for you, his knuckles striking the door. Don’t pretend you don’t hear. Don’t pretend he’s not there. Open the door, Driver Wang.”

As Wang struggles to figure out what is going on, we discover that there’s more to him than being a cab driver, husband and father. He has a complicated past. His father, who worked in government, was largely absent and his mother had mental health issues, so he was sent away to school. Later, his father coldly informed him of her death: “The funeral was three days ago. We didn’t want to interrupt your schooling.”

And so the young Wang ended up in a mental health institution himself – and that’s where he meets the person who he not only develops a special bond with but who will have a huge impact on his life. It’s no wonder that, years after he has left the health-care facility, he begins to suspect this person may be the letter writer and that suspicion drives him even closer to the edge, risking not only his marriage but also his sanity.

Barker’s prose is rich – some sections read like poetry and demand rereading and savouring, but it rarely gets syrupy. The story is always at the forefront, driving the narrative forward – we want to know who is sending the letters, where these twinned souls are heading.

The sensitivity, depth and craft that Barker brings to this work are explained by looking at her background. Her first degree was in philosophy at Leeds University and it was during a two-year stint teaching English in Japan – the only real job she’s had, besides novel writing – that she started writing short stories. She returned to Britain to do an MA in creative writing at the University of Manchester and it was there that she penned her first novel, Sayonara Bar, set in Japan.

By the end of the course she had an agent, a publisher and a two-book deal.

Her second book, The Orientalist and the Ghost, was set in 1950s Malaysia. Those two books did well, but they didn’t shake the world. This one is sure to make an impact and she deserves all the praise – and most likely prize(s) – that will follow.

Original Link: SCMP