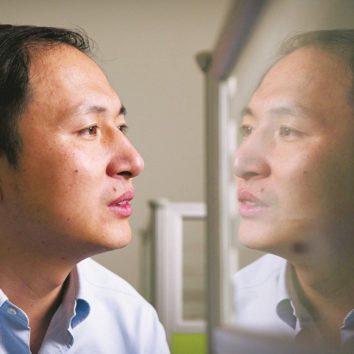

Adam Johnson

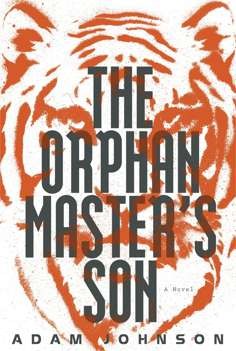

— November 3, 2016The Hong Kong International Literary Festival speaker, who won a Pulitzer Prize for The Orphan Master’s Son, talks about his lonely childhood and why his stories tend to veer towards the bizarre

When Adam Johnson won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, for a novel set in North Korea, many were surprised that an American academic who had spent just five days in the country could write so convincingly and colourfully about the hermit kingdom. Understand a little about the author and his life, though, and it begins to make sense.

THE SUCCESS OF The Orphan Master’s Son (Random House) turned Johnson almost overnight from what he calls a “normal writer” into one with celebrity status.

“North Korea is a topic that people care about around the world, so suddenly I started getting invited everywhere,” says Johnson, a professor of English at Stanford University, in the United States.

But there was a drawback to the international invitations – separated from his family he began to get lonely. The solution? Take them with him.

“Everywhere I go I drag my wife and kids,” says Johnson.

So, when he arrives for the Hong Kong International Literary Festival this week, he’ll do so accompanied by a family entourage of four.

“I’m a writer and [when he disappears into his study] I’ll say to them, ‘I’m going to go off and work’ and it doesn’t seem like work to them, it only seems like I’m missing. It’s only at events like this that they realise maybe what the product of that is,” says Johnson, by Skype from his home in San Francisco.

Growing up in Arizona, he longed to be part of a big family, says the author, sitting around a raucous dinner table. He was an only child, his mother was an only child and his parents divorced when he was eight. The loneliness was all the more acute because his mother, who was establishing a medical practice, was at work much of the time, and even when she wasn’t, she was distant.

Growing up in Arizona, he longed to be part of a big family, says the author, sitting around a raucous dinner table. He was an only child, his mother was an only child and his parents divorced when he was eight. The loneliness was all the more acute because his mother, who was establishing a medical practice, was at work much of the time, and even when she wasn’t, she was distant.

“She was often kind of melancholy. Weekends we would get in her car and drive to Texas or New Mexico and she would listen to Motown and smoke a lot and we would not talk,” says Johnson.

He recalls wandering around the neighbourhood after school and rummaging through the neighbours’ rubbish bins in what he now realises was an attempt to understand the meaning of family.

“I would puzzle over who they were and what their families were like based on what they threw away. I would find something like a magazine and think, ‘Oh, a family reads magazines.’ And then I would press my mom to subscribe to a magazine.”

But his wasn’t an entirely bleak childhood. His father, who worked as a night security guard at the local zoo and had an attraction to the Sonoran Desert, was around in the early years and clearly had a sensitivity and sense of adventure that Johnson shares.

“Even though the desert seemed void of life, my father could always show me there was an ecosystem there if you were willing to see it,” says Johnson.

Before his parents split up, his father would take him to the zoo at sunset to give his mother – a psychologist – a chance to work on her PhD dissertation. Johnson recalls seeing a black rhino getting into difficulty giving birth and his father – ever game – jumping into the pit with a tranquilliser gun.

“My father was always in appreciation mode. We’d listen to the call of the lamas, wonder what they were talking about. We would spend our time robbing the zoo, culling animals and rousting people out of the parking lot who were trying to have sex,” says Johnson. “It was also a deeply magical time.”

Nevertheless, he was often lonely, and his imagination became his best friend and constant companion.

At Arizona State University, Johnson earned a BA in journalism in 1992, but his heart lay in fiction rather than fact. So much so that, midway through his undergraduate degree, his professor staged what Johnson calls “an intervention”, reprimanding him for making things up in the articles he wrote.

“He’d pick a quote out and say, ‘This quote is too good, you must have made it up.’ And I would confess. I would never do that now,” he says.

Johnson juggled courses in journalism and fiction until something shifted in his late 20s, and “everything I wrote […] was dark, funny, absurd and slightly realistic, even if the world is not recognisable”.

One of his absurd stories – a tale about a French fur trapper who joins a team of gay Canadian scientists on a trip to the moon, and gets stranded – won him a fellowship to Stanford University. When the two years of the Stegner Fellowship were up, he began working for the university. And he’s been there for 15 years.

For a fiction writer, teaching at Stanford University is an enviable gig. It is a nurturing environment and gives him the space to do his own writing.

In 2004, Johnson read the newly translated memoir of North Korean defector Kang Chol-hwan, The Aquariums of Pyongyang, and was intrigued by the account of imprisonment in a North Korean labour camp and Kang’s eventual escape from the country.

“As an American, the Korean war is a war we don’t even talk about. We made a TV show about it called M*A*S*H, a comedy. Really, it was a show about drinking martinis more than anything else. I realised my ignorance about that period of history and became quite curious about the place,” says Johnson.

He set out to read everything he could find about North Korea, but most books on the country focused on economics and military and geopolitical issues. Johnson wanted to know what it was like to live there. What did North Koreans have for breakfast? What was it like to go to school in Pyongyang.

He set out to read everything he could find about North Korea, but most books on the country focused on economics and military and geopolitical issues. Johnson wanted to know what it was like to live there. What did North Koreans have for breakfast? What was it like to go to school in Pyongyang.

He began reading about the experiences of defectors in online transcripts posted by NGO and aid workers. These people had gone through famine, worked in factories, witnessed atrocities and made a small mistake that changed their life.

“It seemed like a place where life was being lived in the most vital and dire of circumstances, and we experience only in literature and movies these human dimensions,” says Johnson.

The more he researched North Korea, the more certain Johnson became that the stories were skewed towards the dark. What about the people who were living relatively normal lives outside the labour camps? The people who didn’t defect, who strolled beside the river in Pyongyang and had picnics with their families?

In search of their stories, he applied to Kim Il-sung University, in Pyongyang, offering his services as a visiting scholar, but received no response. He wrote to another university in the capital and offered to host one of its professors at Stanford for a year, but that didn’t work. And then someone suggested speaking to a professor at Lewis & Clark College, in Oregon – Dr Joseph Man-Kyung Ha.

Born in the north of a unified Korea, the business executive turned academic was interested by what Johnson was trying to write.

“He said no one is trying to do this and, by that, he meant trying to project the humanity of North Korea, because it’s so hard for them to get out,” says Johnson. “And he said, ‘I’ll take you there.’

“I think the reason North Koreans allow people in is because they assume it’s such a well-crafted trip, there’s no way you can see anything that will put the regime in a negative light. But they are so insulated that they don’t know what might put them in a negative light.”

What the writer didn’t know was that Ha was approaching the end of his life, which may explain why he was willing to risk his relationships and a lifetime of work in North Korea to take Johnson into the country. Ha died before The Orphan Master’s Son was published.

Johnson’s interest in North Korea became an “obsession”; he found everything fascinating – factory life, the fishing boats, the kidnappings, the tunnels, Mount Baekdu and the capital, Pyongyang. He wanted to put it all into a single story and admits that that is one of the greatest fictions of the novel – no regular North Korean would see all the places described in the book.

Nevertheless, Johnson spins a thoroughly convincing tale. The speculative element, he says, is the psychological dimension – wondering what it’s like to be raised in a totalitarian environment in which you are not the centre of your own self-definition, where you can’t share your true identity and your life is mapped out by others.

A key moment in the crafting of the novel came when he stumbled across a Federal Aviation Administration study into why South Korean airlines have bad safety records. The report cited ageing fleets and poor maintenance, but it noted a couple of examples of crashes in which the co-pilot had noticed mistakes made by the pilot but, instead of correcting them, had chosen to go down with the ship.

“That was really big for my mind, psychologically. It’s counterintuitive, it speaks of a different thinking I wanted to wrap my head around. It made me think that if people were so concerned with the preservation of order, for a short period of time you could probably disrupt that order and no one would say a word,” says Johnson.

That thought shaped the plot, but we’ll leave it there for the benefit of those who haven’t yet read the book.

Johnson spent seven years researching the story and, in its writing, the father of three had lots of emotion to draw on.

Doubters told him to steer clear of the topic – a well-meaning senior colleague at Stanford warned him he was risking his career with a novel about North Korea – and he did question his obsession. But then decided to trust his gut.

“When I become obsessed with Kurt Cobain or Maori taboos or find myself on eBay buying loads of s**t one night, that’s a sign I need to put that into a story,” says Johnson.

“I’m still the guy who wrote a story about Canadanauts and putting a French fur tracker on the moon. I’m going to write my crazy stories no matter what.”

Adam Johnson will appear at two events at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival: “North Korea in Fiction”, moderated by Kate Whitehead, on November 12, 2-3pm, at The Fringe Club, 2 Lower Albert Road, Central; followed by “Should We Visit North Korea?”, a panel discussion, 5-6pm. Tickets are available through festival.org.hk.

Original Link: SCMP