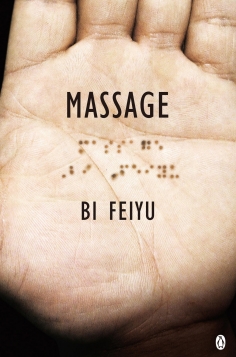

Bi Feiyu opens readers’ eyes to blind masseurs’ world

— May 17, 2015Massage, a translation of Chinese novel that won nation’s top literary prize, examines the relationships among blind masseurs and with the sighted

What does physical beauty mean to someone who can’t see? It’s an intriguing question – for both the sighted and the blind – and one of the many aspects of life for the visually impaired Bi Feiyu explores in his sensitive yet frank novel Massage.

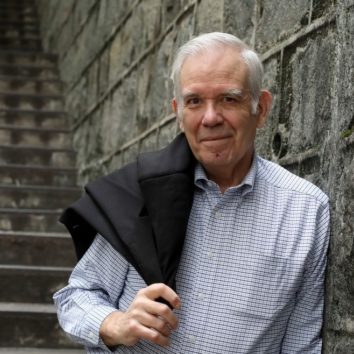

Few authors have written from the perspective of the blind. Circumstance led Bi, winner of the 2010 Man Asian Literary Prize, to that world. His father was ousted as a “rightist” and the family sent to the countryside. After a nomadic childhood, Bi escaped life on a farm when he was accepted to study literature at Yangzhou Normal University. After graduation in 1987, he was sent to work at a training school for teachers of the blind and deaf in a remote spot outside Nanjing. This was an order – he had no say in his placement.

He worked there until 1992 when he left to join the Nanjing Daily as a reporter. But years later in 2003, following a serious shoulder injury, a friend suggested he visit a massage clinic that employed blind masseurs. After a month of treatment his injury healed and he developed close friendships with some of the blind masseurs. These experiences feed into Massage and give it authenticity.

First published in Chinese in 2008 and winner of the nation’s top award for literature, the Mao Dun Literary Prize, this novel about China’s blind masseurs is Bi’s latest work to be translated into English by his long-standing translator, Howard Goldblatt, and Sylvia Lin Li-chun.

The story follows the lives of 15 tui na practitioners. Tui na is a traditional form of pressure-point massage and one of the few career options open to China’s visually impaired. First we meet Wang Daifu where he’s working at a tui na centre in Shenzhen. It’s 2001 and business is good. Wang has plenty of big-tipping wealthy clients from Hong Kong, one of whom gives him his first US dollar bills. He immediately notices the texture and size of the notes are different and thinks he’s been cheated, but then discovers the greenbacks are more valuable than the yuan or the Hong Kong dollar.

The story follows the lives of 15 tui na practitioners. Tui na is a traditional form of pressure-point massage and one of the few career options open to China’s visually impaired. First we meet Wang Daifu where he’s working at a tui na centre in Shenzhen. It’s 2001 and business is good. Wang has plenty of big-tipping wealthy clients from Hong Kong, one of whom gives him his first US dollar bills. He immediately notices the texture and size of the notes are different and thinks he’s been cheated, but then discovers the greenbacks are more valuable than the yuan or the Hong Kong dollar.

This gives him a taste for money – and he wants more. “Crazed, that’s what money was. Unreasonable. One bill after another, like flying carpets, leaping and gliding through the air. They soared high, they turned and tumbled, then they dove earthward with a whistle to settle right into Wang Daifu’s hands.”

Amid the good times and easy cash, Wang falls in love with a blind masseuse named Xiao Kong. He falls for her hard and wants to give her the best. His dream is to open his own tuina centre and marry Xiao, bestowing on her the coveted status of the “boss’ wife”. But for this he needs even more money. Greedy for cash, he invests in the stock market – and loses.

Wang returns to his hometown of Nanjing with Xiao – now his fiancee – and they stay with his parents until his good-for-nothing gambler brother makes life uncomfortable. Suppressing his pride, he calls Sha Fuming, a friend and former classmate at the school for the blind where they learned their craft, for a job at the tuina centre he has opened with a partner. Sha gladly gives both Wang and Xiao jobs and so the reader is introduced to the masseurs who work here. We meet them in turn, feeling our way through the darkness, and as Bi carefully fleshes out their complex back stories and connections they become real to the reader.

For those who work at the massage parlour, there is an unvarying daily pattern as they shuttle backwards and forwards between the centre and their dormitory, but their private lives and the increasingly complicated relationships are anything but monotonous.

Bi has said he didn’t write the novel to highlight the plight of China’s 17 million visually impaired citizens, although he’s happy it has gone some way to doing this. When a movie based on the book was released last year and picked up awards at the Berlin Film Festival and the Golden Horse Awards in Taiwan, it helped put the social issue on the map.

Bi wrote the book because he wanted to reveal something new about the interpersonal relationships between the blind. And he has. Take Du Hong, one of the youngest masseuses at the centre. As a student at the blind school, she had her heart set on singing but her teacher talked her out of it – “What’s so great about a blind girl singing?” – and instead took up the piano. She practised hard, determined to prove herself, but at her first concert she stumbled through the piece and realised she had let herself down. When, at the end of her performance, the audience gave her a standing ovation, her heart sank because she knew the applause had nothing to do with her playing and everything to do with her impairment.

Du is not the best masseuse at the centre, but she’s the most popular with clients. She is also – and by no means unrelated – strikingly attractive. This we – and the other masseurs – learn when a film director and his crew visit. The filmmaker remarks loudly on her good looks and it unsettles the others: Du has been singled out for attention, there is something special about her – and they can’t see or understand it.

The blind must use the assumptions of the sighted to build their world view.

Sha is the most affected by this: “A question surfaced and intensified in his mind, a very serious question: Exactly what is beauty? He could feel his mind growing unhinged as he was mired in profound anxiety.”

He deeply ponders the nature of beauty and falls in love with Du, or perhaps it’s just the idea of her. The blind may not be able to see, but they soon pick up that the boss has feelings for Du and it begins to divide the staff between Sha and his business partner, Zhang Zongqi. The politics of this divide forms the framework of the novel and while it drives the story forward it’s the characters themselves who provide the real joy for the reader.

Bi paints an intimate portrait of each character. We learn of their dreams and successes as well as their failures and humiliations. None is intended to inspire pity, but rather compassion as they reveal their secrets and grapple with their sense of identity. We learn that there is a big difference between being born blind and losing your sight later in life.

Xiao Ma was an adult when he lost his sight in a traffic accident. We learn that those years of sightedness don’t necessarily make for an easier life as a blind person. Knowing what it means to see while being blind is described as purgatory. This explains Xiao Ma’s silence, always on the fringes of the group. He shares a bunk bed with Wang, taking the lower bunk, and develops a serious crush on Wang’s fiancee. When Xiao Kong notices the infatuation and realises she has inadvertently encouraged it, she keeps her distance from him. Xiao Ma becomes even more caught up in his own world and eventually finds comfort at a brothel where he becomes attached to one prostitute in particular.

As the individual stories unravel, they become even more closely interwoven with the others at the centre. Bi doesn’t paint a romantic picture of the blind nor is it one of despair. Instead we discover a group of real people facing human issues.

Zhang, the co-owner of the centre, has a childhood fear of being poisoned thanks to a wicked stepmother who threatened to poison his food if he complained about her to his father. Zhang insists on hiring the centre’s chef, but even so he waits for the others to begin eating before he tucks in. And then there’s Jin Yan, whose blindness crept up slowly in her early teens. She spent her remaining years of sightedness watching every film and reading every book she could find that featured a wedding. At the centre, she spends most of her time imagining a romantic wedding day.

Bi’s cast of characters do not define themselves by their visual impairment. Most of them have accepted it and are getting on with their lives as best they can with their own fears, needs and desires.

Original link: SCMP