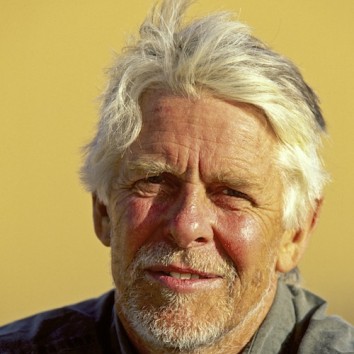

The Italian priest tells Kate Whitehead how became fascinated by China, was eventually barred, and how he has fought for the rights of the disadvantaged

GREAT LEAP My parents are from Milan, Italy. My father worked for a fur company and my mother worked in a factory. She was very active and started her own union, and encouraged my father to join the union in his factory. I remember my father striking in the late 1960s and fighting for a bonus.

I sang in the Milan Choir from the age of nine – every Sunday for four years we sang songs in Latin. Aged 14, I entered the seminary of the local Milan diocese, to become a priest. One day, our secondary school teacher at the seminary asked us to prepare an exhibition on a continent. Our group was given Asia and I was in charge of China. It was the first I knew of China and I was fascinated – it was around the time of the Great Leap Forward and everyone was talking about it positively then.

When I was 18, I shifted to the Pime (Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions), to which I still belong. With the support of a lawyer, we created the first social action group in Milan. Young people involved in politics and social action were called Maoists at that time. To say “he is a Maoist” was to say “he is involved in social action”. During the Cultural Revolution we saw the so-called proletariat changing: they were more interested in serving the people than getting money or living a comfortable life. I thought, “Why in China is there such a spirit?”

MASS AWAKENING I was 26 when I arrived in Hong Kong, in 1974, and Mao was still alive. In 1976, when he died, China shifted to revisionism, so it was a kind of disappointment. When I came to Hong Kong, my hope was to live according to (communist) ideas, to live with the common people. All the new Pime arrivals stayed at a place in Clear Water Bay, we learned Cantonese and it was very comfortable – but I was lonely. After a few months I moved to Diamond Hill, which was a squatter area. The local priest there said, “You have to say the mass in Chinese by yourself.” So I practised, writing down the sounds, and within nine months of being in Hong Kong, I was giving mass in Cantonese.

FIRED UP I worked in 14 factories over 12 years. At first, I got a job at a garment factory in San Po Kong. The pay was HK$15 a day; after six months it was increased to HK$15.50. Even if you stay a long time in a factory you don’t get any benefits. Sometimes I was dismissed because I protested – especially about safety at work, because at that time there were many fires and people would die. I would say mass at 7am then go to work at 8.30am. On Sundays, I would go to church and say mass again.

I’d been in Hong Kong for less than a year when there was a fire in a nearby squatter area. The small factory owners there organised themselves to get compensation, but the squatter people couldn’t, so I helped them. A month later there was another fire in another squatter settlement. We approached Elsie Tu (a British-born social activist and former Hong Kong legislator) to help fight for our rights.

ALL AT SEA In 1978, some of the squatters told me about their relatives who lived on boats in Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter – their boats were sinking. On Christmas Eve that year we asked the government to give 200 former fishermen homes because their boats were rotten and they couldn’t go on the high sea any more, so they had to work on land. On January 7, 1979, we took 76 people to petition the government, but were stopped by the police and arrested. Later in court, the boat people were freed but the 11 protesters were given 18-month suspended sentences.

ALL AT SEA In 1978, some of the squatters told me about their relatives who lived on boats in Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter – their boats were sinking. On Christmas Eve that year we asked the government to give 200 former fishermen homes because their boats were rotten and they couldn’t go on the high sea any more, so they had to work on land. On January 7, 1979, we took 76 people to petition the government, but were stopped by the police and arrested. Later in court, the boat people were freed but the 11 protesters were given 18-month suspended sentences.

In 1979, I started to live on a boat in Yau Ma Tei, to be closer to the people I was helping. A year later, another priest joined me. We lived there for 10 years – the boat sank twice and we repaired it. It used to smell terrible at low tide.

BOAT BRIDES Many of the former fishermen were illiterate and poor. They found it hard to find a wife in Hong Kong, so many married girls from villages in southern China. These “boat brides”, as they were called, weren’t allowed on the land, they had been smuggled into Hong Kong and due to a very odd rule at the time, if they were caught on land they would be sent back to the mainland – but they could live on the boats. If the boat brides had children it was illegal for them to take their offspring to school.

We petitioned for 14 of these boat brides to be given right of abode. When I went back to Italy, as I did every five years, I went to the United Nations in Rome and then to London to speak to Amnesty International and women’s groups. When I returned to Hong Kong in February 1986, we had a press conference and threatened to go on hunger strike if the government didn’t resolve the boat bride issue by Easter. After 3½ days, the government said it would give the right of abode to 1,000 boat brides.

BACK ON DRY LAND In 1989, the former fishermen were given housing and so all of us moved on land. I began living with the street sleepers behind Yau Ma Tei police station. I didn’t (and still don’t) wear the uniform of a priest – that’s in line with liberation theology, to stay with the common people. I worked in a factory during the day, washed in the public baths and slept on the street at night on a nylon camp bed. After all, St Francis became a beggar and lived as a homeless person. When I went back to Italy in 1990 for a holiday, it felt very strange to sleep in a room, after a year of sleeping in the open.

In 1991, I moved to China and lived there for 20 years, at first in the south and later in the central regions. I worked as an English teacher and a volunteer. In 2011, the church in Rome excommunicated a bishop ordained by the Chinese state and Beijing took revenge by putting 23 of us on a blacklist. It threw us out of the country. Since then, I’ve been back in Hong Kong and have been very involved visiting people in prison and setting up a school for refugees. I hope to return to China. Perhaps they will let me back next year.

Original Link: SCMP